Landscape as (Self-) Portrait

We have updated the Itineraries section of our website, in which guests are invited to take personal journeys through our collection, with a deep dive into landscape painting by art historian and journalist Anatxu Zabalbeascoa. She explains that she is looking to switch the focus from landscape as a background or filler for canvases to its use as a core element that takes centre stage, often as a reflection of the state of mind of the artist and a mirror held up to their "inner eye".

She traces a path from back to front and from outside to inside as she examines the evolution of the genre throughout history, highlighting that it is in fact impossible to portray a place without portraying oneself, without leaving an imprint of what one feels as an artist on producing a painting, and of the historical and cultural context in which each work is painted. "This selection of canvases, watercolours, collages and photographs is intended to show that when one depicts a place one leaves a part of oneself in it", she writes.

She has chosen landscapes from the Banco de España Collection which date from the early 16th century to the present day. Through them, she points out the many things that may underlie a picture of a landscape: evocation and memory, hope or fear for the future, a call to live in the moment, feelings of uprootedness, social criticism, finding oneself, coming to terms with the fleeting nature of life and our role as a part of nature, etc.

Joos van Cleve: Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1500)

Joos van Cleve: Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi (c. 1500)

The journey begins with Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi by Joos van Cleve, "one of the first artists to use landscapes, rather than just backgrounds, as a backdrop in his works", states Ms. Zabalbeascoa in the essay![]() that goes along with her itinerary. Except for this piece and the three that follow it Landscape with Christ and the Pharisees by Pierre Patel (The Elder), Perspective with Portico and Garden by Castellón-born Vicente Giner and Landscape with Carts at a Ford by an unknown Dutch artist), the works selected date from the 19th, 20th and, in the last case, 21st centuries.

that goes along with her itinerary. Except for this piece and the three that follow it Landscape with Christ and the Pharisees by Pierre Patel (The Elder), Perspective with Portico and Garden by Castellón-born Vicente Giner and Landscape with Carts at a Ford by an unknown Dutch artist), the works selected date from the 19th, 20th and, in the last case, 21st centuries.

George Elgar Hicks: Mountainous Landscape(c. 1850)

George Elgar Hicks: Mountainous Landscape(c. 1850)

In Mountainous Landscape (c.1850) by George Elgar Hicks and Girona Landscape (1884) by Santiago Rusiñol there is a metaphorical dimension to the way in which nature is interpreted that hints at the states of mind of the artists. Settings are seen as a way of looking within oneself to express feelings of loneliness or fear at an unknown future, as in the case of Landscape (The Old Vilanova Road) by Ramón Casas i Carbó, painted in 1890, which shows a cutting through a hill to make way for progress in the form of railway tracks.

The next landscape selected by Ms. Zabalbeascoa date from the period of impasse at the turn of the 20th century: the water-colour Landscape with Trees (1900-1906) by Julio González. In the former the landscape is shown in a faded, expressionist style, while the latter hints at the path that was to lead the artist to become one of Spain's greatest sculptors more than twenty years later.

The influence of Cubism and the vitalist spirit of the early avant garde are plain to see in Paris (1917) by Alfonso de Olivares, an urban landscape "like a poster announcing the future". That future, however, seems far removed from the Castilian landscape painted by Joaquín Vaqueros Palacios in Clouds over Castile more than forty years later in 1960. Here the landscape is more constructed than painted, perhaps as a result of the artist's training as an architect. It is a figurative abstraction in which "reality is more palpable than imaginable". Carmen Laffón takes a very different look at that reality in Seville (1962), which captures a peaceful, domestic moment in time that can be seen almost as a still-life (a genre that played a major role in the oeuvre of this Seville-born artist, who died in 2021).

Alfonso de Olivares: Paris (1917) | Joaquín Vaqueros Palacios: Clouds over Castile (1960)

Alfonso de Olivares: Paris (1917) | Joaquín Vaqueros Palacios: Clouds over Castile (1960)

There is quite a difference between Laffón's calm, domestic landscape and the disturbing Scene with Boats (c. 1964) by Pancho Cossío, "where everything seems to disappear". The scene seems to be painted with sand rather than gouache. It is one of the last works painted by Cossío, who experimented with abstraction and created a style that can be thought of as post-Cubist. The work of Godofredo Ortega Muñoz, one of Spain’s finest landscape painters of the last century, is calmer and can be regarded as half-way between traditional art and the avant-garde. A case in point is Olive Trees and Holm Oaks (1964), which Zabalbeascoa describes as portraying "the noble sobriety of nature, which works with the materials at hand, and blooms with so little". Benjamín Palencia was another great landscape artist. The work by him selected here is Looking West (Landscape) [1972], a canvas from his later period which depicts a re-encounter on two levels: of the artist with his home region (Castile) and of the artist with himself.

![Pancho Cossío: Escena con barcos (c. 1964) | Benjamin Palencia: Poniente (Paisaje) [1972]](/f/webca/ADS/Noticias/imgtxt05.jpg) Pancho Cossío: Scene with Boats (c. 1964) | Benjamin Palencia: Looking West (Landscape)[1972]

Pancho Cossío: Scene with Boats (c. 1964) | Benjamin Palencia: Looking West (Landscape)[1972]

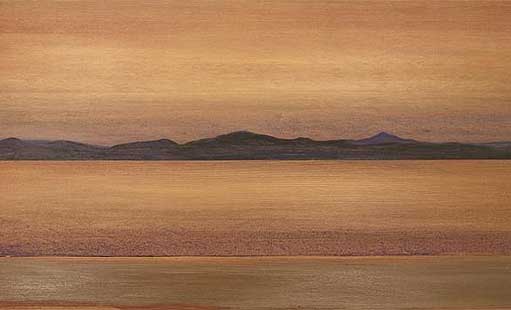

The Fauvist force of Palencia's picture gives way to an enigmatic oil painting by Juan Manuel Díaz Caneja, Landscape (1974), which could be an aerial view of the fields of Castile but could equally be a stone wall. Díaz Caneja was born in Palencia and was a student of Vázquez Díaz. This work is from his later period, when he simplified and pared back his style. A similar path towards simplicity was taken by Albert Ràfols-Casamada, whom Ms. Zabalbeascoa says "painted colours first and foremost". A good example of this is his oil painting Yellow Sea (1979), which is "so tenuous that it looks like a water-colour".

This path towards simplicity as a way of obtaining (self-) knowledge is linked to the search for flow and the acceptance of change as the essence of nature that characterises Taoism, which is prominent in the later output of Manuel Hernández Mompó. Participating in Nature (1980) dates from that period. It is an imposing work that stands three metres high and evidences how the artist was striving to expand his work. Another fine example of "expanded painting" (or in this case "expanded landscape") is Three Pieces of Wood (1986) by Perejaume, in which a set of three pieces of wood constructs a landscape. The horizontal undulations of the micro-landscape "sealed within the material" is similar to that depicted (or reinvented) by José Beulás in Tierz (Huesca) [1985]. Beulás was born in Santa Colomá de Gramanet (Barcelona), and this is one of the numerous paintings that he produced of the landscape of Huesca province, the starkness and roundness of which captivated him from an early age.

Albert Ràfols-Casamada: Yellow Sea (1979) | Miquel Barceló: Quelques herbes(1986)

Albert Ràfols-Casamada: Yellow Sea (1979) | Miquel Barceló: Quelques herbes(1986)

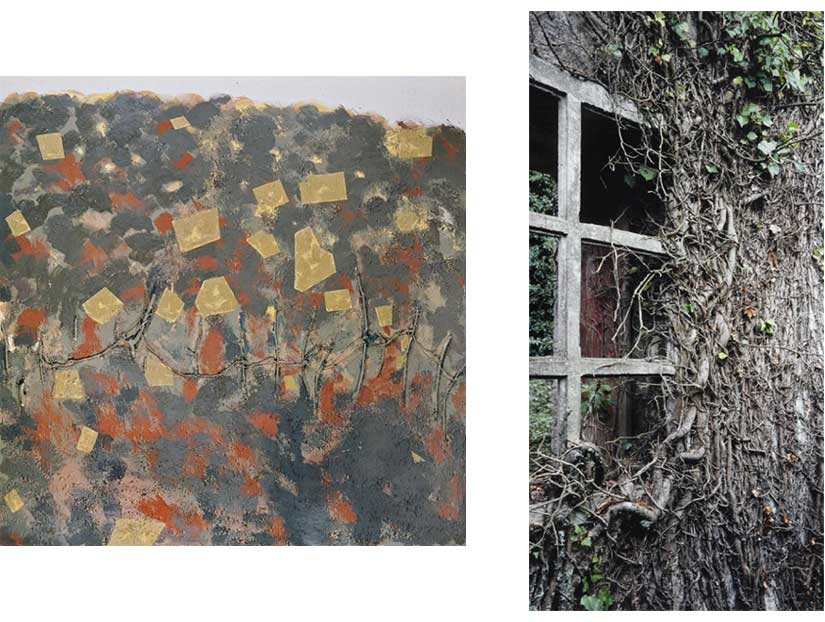

In the itinerary drawn up by Ms. Zabalbeascoa the oil by Beulás comes just before Quelques herbes (1986), in which nature is a palpable element. In it, Miquel Barceló evidences the "material construction, the metamorphosis that takes place in all painting". The same material aspect can be seen in Turia (1987), a collage in which Carmen Calvo poetically maps the river that runs through her home town, acting as an archaeologist or gleaner of everyday objects. The same goes for the small oil painting Landscape (1992) by Catalan artist Carmen Pinart, whose work is characterised by the use of oil-paint and gold-leaf on wood. Here she dazzles spectators with a golden landscape with hints of the figurative and the organic.

Carmen Calvo Turia(1987) | Monserrat Soto: Untitled. Huella 12(2004)

Carmen Calvo Turia(1987) | Monserrat Soto: Untitled. Huella 12(2004)

As the last item in her itinerary Anatxu Zabalbeascoa has made a curious choice. It is not a painting but a photograph: Untitled. Huella 12 (2004) by Montserrat Soto, one of her series Huellas held in the Collection. Zabalbeascoa writes that this picture can be seen as a contemporary ruin or as a metaphor for the passage of time that reveals something which, in our hearts, we already know: what remains, what returns again and again, is nature. And it does so precisely because it changes and is constantly transforming itself.