Francisco de Cabarrús. Rise and fall of a key player in the history of the Banco de España

Francisco de Cabarrús y Lalanne was a charismatic, multi-talented, controversial man with an extraordinary ability for business and social relations. He was a key figure in the political and economic history of Spain in the late 18th and very early 19th centuries. He was the brain behind the creation of the Banco Nacional de San Carlos, which is seen as the first forerunner of the Banco de España, and of many other major financial projects in the latter years of the reign of King Charles III. He was awarded the titles of Viscount of Rambouillet and Count of Cabarrús. He rose to power very quickly, but fell from grace even faster.

He was born in Bayonne (France) in 1752, into a family of traders and seafarers who hailed originally from Navarre, and began his career in business in Valencia the early 1770s. He subsequently moved to Carabanchel de Arriba, where he managed a successful soap factory owned by a relative of his wife. As he prospered in trade and banking, he began to move in the circles where political power was wielded. In 1776 he joined the RSEMAP![]() ["Madrid Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country"], a liberal philanthropic institution modelled on the ideas of the Enlightenment, where he met Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, with whom he would remain close friends until the Peninsular War.

["Madrid Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country"], a liberal philanthropic institution modelled on the ideas of the Enlightenment, where he met Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, with whom he would remain close friends until the Peninsular War.

When Spain and France came into conflict with Britain following the American War of Independence, Francisco de Cabarrús suggested to the Count of Gausa, who was Treasury Minister at the time, that rising public expenditure should be offset by issuing government securities called vales reales ["Royal Bonds"]. These would be placed in circulation by the Banco Nacional de San Carlos, which, as Paloma Gómez Pastor explains, was created as a result of Cabarrús's insistence that there should be an "official credit institute" that could advance funds to the State against these bonds, handle payments for the Crown abroad, combat usury and provide credit for trade and industry.

Francisco de Goya: Francisco de Cabarrús (c. 1788)

Francisco de Goya: Francisco de Cabarrús (c. 1788)

Cabarrús became one of the most socially and economically influential figures in the Spain of his time. He was appointed Honorary Director of the Banco de San Carlos and it was under his auspices that the custom of having portraits of directors painted was begun. That custom was broken at the end of the 19th century, following the death of Charles III, when the political upheavals that followed the French Revolution gave rise to a wave of anti-Enlightenment opinion. This set him on the path to a fall from grace, along with his friends and protégés. On his way up the political and financial ladder Cabarrús had made powerful enemies, and now he was not just dismissed from his post as director but actually imprisoned, accused of smuggling in his youth.

Among his friends and protégés was Francisco de Goya, who painted his portrait in 1788. This was Goya's last portrait for the Banco de San Carlos. It depicts him standing, dressed in clothes of bright green silk (a colour associated with wealth) highlighted in gold which made his bulky figure stand out against a background in half-shadow reminiscent of the works of Velázquez. Manuela Mena points out that he is shown with no staff of command or other trappings of power associated with Spain's Ancien Régime, thus stressing his membership of a new social class - the bourgeoisie - which was gaining ground on all fronts. "He did not have an illustrious past, and seems here to emerge from the darkness of history", writes Mena, "but he stands alone in his own strength and weight, casting a clear shadow on the ground that hints at forward movement through Goya’s depiction of his coat and the position of his leg. The impression is of a figure driven forward as if by centrifugal force towards a new project".

Agustín Esteve y Marqués: Portrait of Francisco Cabarrús (c. 1798) | Bartolomé Maura y Montaner. Portrait of Francisco Cabarrús(1895)

Agustín Esteve y Marqués: Portrait of Francisco Cabarrús (c. 1798) | Bartolomé Maura y Montaner. Portrait of Francisco Cabarrús(1895)

This portrait is one of the works on show at the exhibition 2328 reales de vellón, which looks at the origins of the Banco de España Collection. The Collection also contains two more works featuring Cabarrús. One is a portrait by Valencia-born Agustín Esteve y Marqués, painted in the late 1790s, which shows him sitting at a desk on which a number of books and documents can be seen. Virginia Albarrán Martín describes them as a "compendium of his politcal and economic thinking". The other is a circular sketch drawn a century later by Bartolomé Maura y Montaner which is an almost life-size copy of the upper part of the full-body portrait by Esteve y Marqués. This sketch was used on the 1000 Peseta note issued by the Bank of Spain in 1898.

The portrait by Esteve y Marqués, which was thought for many years to be by Goya, was probably painted around 1798, when Francisco de Cabarrús had been reinstated as Director of the Banco Nacional de San Carlos after spending five years in prison without trial. However his luck changed again shortly afterwards, when Manuel Godoy formed an alliance with the most reactionary factions to recover power and dismissed his "enlightened" ministers. Cabarrús then moved to Barcelona, where he largely abandoned politics and focused on a number of industrial projects.

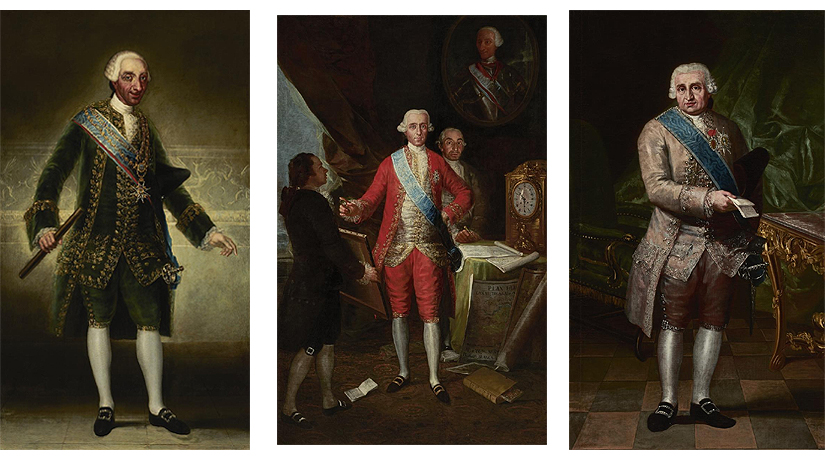

Francisco de Goya: Portraits of King Charles III (c. 1786), of José Moñino y Redondo, First Count of Floridablanca (1783) and of Miguel de Múzquiz y Goyeneche, First Count of Gausa and First Marquis of Villar de Ladrón (1783)

Francisco de Goya: Portraits of King Charles III (c. 1786), of José Moñino y Redondo, First Count of Floridablanca (1783) and of Miguel de Múzquiz y Goyeneche, First Count of Gausa and First Marquis of Villar de Ladrón (1783)

On the outbreak of the Peninsular War in 1808 he initially supported the popular uprising against the French forces, but eventually joined the cause of Joseph Bonaparte, who made him Treasury Minister in July that year. He continued to hold this post until his death in Seville on 27 April 1810. He was initially buried in a pantheon in the chapel of La Concepción at Seville Cathedral, close to that of the Count of Floridablanca, another key figure in the origin of the Banco de España who also had his portrait painted by Goya. However in one last, dramatic twist in his incident-filled story, in 1814, after the end of the war, his remains were exhumed after he was found to have committed high treason by participating in the government of Joseph Bonaparte. He was reinterred in a common grave in the courtyard of the Patio de los Naranjos, a place reserved for those put to death as criminals.