Out of Shot. When Omission Reveals as Much as Portrayal

Rogelio López Cuenca and Elo Vega argue that the items in the Banco de España’s collection — accumulated over more than 200 years — constitute a valuable case study for tracing ‘different inflections in the way women are shown (or not shown)’ and other manifestations of ‘otherness’ in art. This is the premise of L.Q.N.H., the latest in our series of Itineraries, in which we invite different authors to design their own personal ‘tours’ of our collection. The pictures in the itinerary, and the accompanying essay![]() , can all be viewed on our website. The authors have selected nineteen works from different periods, styles and formats, analysing them not only for what they reveal, but also for what they leave out — all the things they consciously or unconsciously remove or omit.

, can all be viewed on our website. The authors have selected nineteen works from different periods, styles and formats, analysing them not only for what they reveal, but also for what they leave out — all the things they consciously or unconsciously remove or omit.

![María Eugenia de Beer: Cuaderno de aves para el príncipe Baltasar Carlos [c. 1637]](/f/webca/ADS/Noticias/NotItinerLQNH_txt01.jpg) María Eugenia de Beer: Notebook of Birds for Prince Balthasar Charles [c. 1637]

María Eugenia de Beer: Notebook of Birds for Prince Balthasar Charles [c. 1637]

When looking at the collection’s historical section through contemporary eyes — note López Cuenca and Elo Vega — we are struck by the fact that ‘leaving to one side the allegories and mythological characters, the only real women are monarchs’. This iconographic reductionism is matched by an even more revealing paucity of female artists, a general trend in art until well into the last century. In her influential essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (1971), historian Linda Nochlin blamed this imbalance on the difficulties women faced in reconciling their careers with the social mandates of marriage, motherhood and care. A good example can be seen in the prematurely truncated career of Marie Eugenie de Beer, author of Notebook of Birds for Prince Balthasar Charles, the earliest work by a woman in the collection.

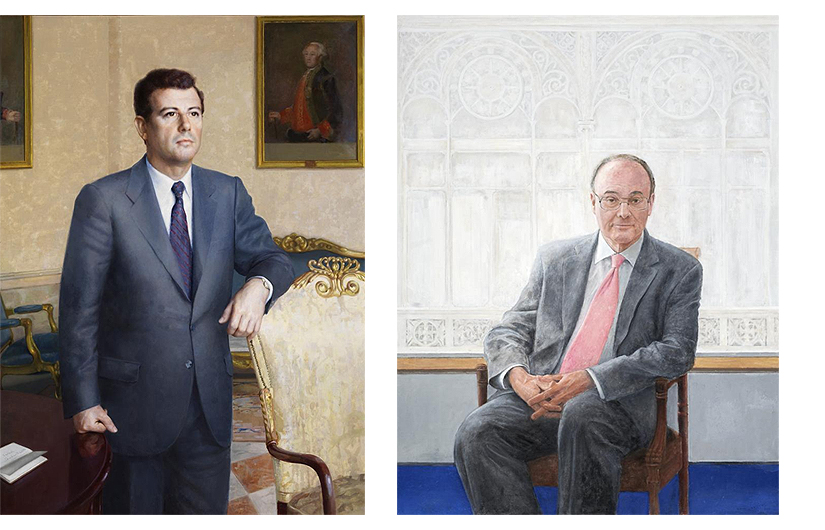

Isabel Quintanilla: Portrait of José Ramón Álvarez-Rendueles (1985) | Carmen Laffón: Portrait of Luis María Linde (2020)

Isabel Quintanilla: Portrait of José Ramón Álvarez-Rendueles (1985) | Carmen Laffón: Portrait of Luis María Linde (2020)

It was not until the 1980s that the collection first began to acquire works by women artists on a regular basis. The first portrait of a bank governor by a female artist dates from 1985, when Isabel Quintanilla painted José Ramón Álvarez-Rendueles. The bank went on to commission three more — of Mariano Rubio, Luis Ángel Rojo and Luis María Linde — all from Carmen Laffón. The portraits of governors and directors (all men, incidentally) contain a plethora of books. In iconographic terms, books have traditionally functioned as a mark of prestige and authority. To some extent, that symbolic role is subverted in Untitled (from the ‘Contemporaneous’ series), a photo by Alicia Martín depicting a toppling pile of books. As López Cuenca and Vega write, it serves as an allegory of the ‘collapse of the edifice of the pretentious certainties of Eurocentric modernity’.

Alicia Martín: Untitled (from the ‘Contemporaneous’ series) (2000)

Alicia Martín: Untitled (from the ‘Contemporaneous’ series) (2000)

Another work that might also be described as a ‘contemporary vanitas’ is Sara Ramo’s Contract, a collage in which the artist fashions a mask from cuttings taken from the Financial Times. By turning a symbol of modernity (a newspaper) into a pre-modern fetish (a mask), Ramo rebuts the arrogance of colonial logic and its paternalistic vision. In a similar vein, Eva Lootz’s work expresses ‘a vindication of materiality, of the corporeal dimension of signs’. Her Cup is also a metaphor for the female body as a mere vessel, the role traditionally assigned to it by ‘the social machinery of the patriarchy’.

Sara Ramo: Contract (2016) | Eva Lootz: Cup (1990)

Sara Ramo: Contract (2016) | Eva Lootz: Cup (1990)

Starting from this allusion to women as subjects without agency, López Cuenca and Vega’s itinerary steps back in time to examine four works that show the way in which this subordination has been naturalised historically: Cornelis van Cleve’s oil painting Madonna of the Lily, the oldest piece in the selection; the nineteenth-century portrait Maria Christina of Austria with the Infant Alfonso XIII by Manuel Yus y Colas; and two paintings from the 1950s, The Land by Joaquim Sunyer and The Sea, by Daniel Vázquez Díaz.

Cornelis Van Cleve: Madonna of the Lily (c. 1550) | Manuel Yus y Colas: Portrait of María Christina of Austria with the infant Alfonso XIII (1887) | Joaquim Sunyer: The Land (1952) | Daniel Vázquez Díaz: The Sea (1955)

Cornelis Van Cleve: Madonna of the Lily (c. 1550) | Manuel Yus y Colas: Portrait of María Christina of Austria with the infant Alfonso XIII (1887) | Joaquim Sunyer: The Land (1952) | Daniel Vázquez Díaz: The Sea (1955)

The next work in the itinerary is A Feminine Touch (Serviette, Silicon and Cotton Bud), in which artist Ana Prada criticises the traditional relegation of women to the domestic sphere, using a subtle exercise of recontextualisation. In an ironic sideswipe, she alludes not only to the idea of submission and docility, but also to the social pressure to ‘conform to the conventional canon of mandatory beauty’. López Cuenca and Vega remind us that the canon of male ‘beauty’ has traditionally been detached from explicit corporeality or physical beauty. Instead, it is linked to material ostentation and — following the triumph of bourgeois morality — to the projection of an image of virility defined by virtues such as moderation, respectability, good sense and severity. These values are paradigmatically encapsulated in the figure of a ‘besuited gentleman’ — such as José Echegaray in the monument sculpted by Lorenzo Coullaut Valera in 1925.

Ana Prada: A Feminine Touch (Serviette, Silicon and Cotton Bud) (2004)

Ana Prada: A Feminine Touch (Serviette, Silicon and Cotton Bud) (2004)

In their essay, López Cuenca and Vega argue that the ‘characterisation of women as being somehow closer to nature and the animal state, than to culture’ is further reinforced when it overlaps with other vectors, ‘such as class and race’. For an example, we need only look at America or Cuba, one of the pictures painted in 1935 by José María Sert for the ballroom of the Venetian palazzo of aristocrat Alejo Mdivani. It includes the only depiction of a black woman in the entire historical section of the Banco de España collection. In a very different way, blackness as otherness also features in Maria Loboda’s photo series The Ngombo, which is structured around the handbag, an accessory which operates almost as a ‘a metonym of the feminine’.

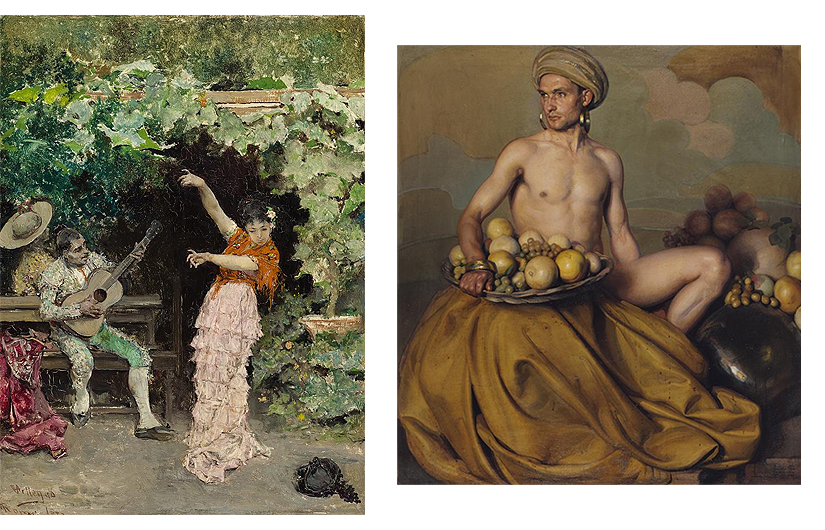

José Villegas y Cordero: Andalusian Dance with Bower (1890) | Gabriel Morcillo Raya: God of Fruit (1936)

José Villegas y Cordero: Andalusian Dance with Bower (1890) | Gabriel Morcillo Raya: God of Fruit (1936)

López Cuenca and Vega remind us that, in Spain, ethnic and cultural otherness are embodied by the Roma, or gitana, community. And if there is one cultural expression that we particularly associate with this group, then it is flamenco, a central feature in the next work in the itinerary: Andalusian Dance with Bower. This genre painting by José Villegas y Cordero dates from 1890, at the height of Andalusia’s appeal as an artistic theme. The authors believe this trend is inseparable from the successive operations of expropriation, reappropriation and exploitation — both symbolic and material — of the ‘territories of the other’ and of subaltern communities, a process which began during the eighteenth-century enlightenment and continues to this day, albeit in a new guise and with new rhetoric.

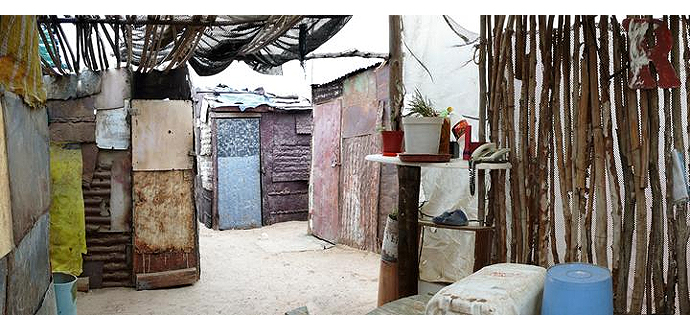

Montserrat Soto: Invasion Succession 20 (2011)

Montserrat Soto: Invasion Succession 20 (2011)

The persistence of this trend is reflected in a photo from Montserrat Soto’s series Invasion Succession. The exclusion and dispossession hinted at by the empty scene could be a reference to agricultural labour, a sector that employs many North African workers. Here it is worth remembering that ‘Moorishness’ constitutes one of the basic pillars of the hegemonic imaginary of Spanish identity, both as a nemesis but also as an exoticised vernacular reference. Spain’s own variant on orientalism developed in the second half of the nineteenth century, a product of the Hispano-Moroccan War, and spawned a vast volume of literary and artistic work with profoundly colonialist associations. The penultimate work in the selection, Gabriel Morcillo’s oil painting God of Fruit, forms part of this legacy.

Maria Loboda: The Ngombo (Series) (2016) | Helena Almeida: To Seduce (2002)

Maria Loboda: The Ngombo (Series) (2016) | Helena Almeida: To Seduce (2002)

In the conclusion to their essay![]() , López Cuenca and Vega quote sociologist Jan Nederveen Pietersen to reinforce their thesis that images of the ‘Other’ do not document his or her reality; rather they are a projection of the concerns, worries, obsessions, fears and fantasies of the society that produces and consumes them. This might explain why so many female artists choose not to include images of women in their works. At most, they are depicted only in fragmentary form, as in Helena Almeida’s disturbing photograph Seduzir, which ends the itinerary. Underlying this decision not to ‘be explicit’, to work with what ‘stands outside, in the shadows’, is a desire to escape from the inherited framework and contribute to creating a new iconography capable of subverting the ‘category of “woman” as an instrument of domination’.

, López Cuenca and Vega quote sociologist Jan Nederveen Pietersen to reinforce their thesis that images of the ‘Other’ do not document his or her reality; rather they are a projection of the concerns, worries, obsessions, fears and fantasies of the society that produces and consumes them. This might explain why so many female artists choose not to include images of women in their works. At most, they are depicted only in fragmentary form, as in Helena Almeida’s disturbing photograph Seduzir, which ends the itinerary. Underlying this decision not to ‘be explicit’, to work with what ‘stands outside, in the shadows’, is a desire to escape from the inherited framework and contribute to creating a new iconography capable of subverting the ‘category of “woman” as an instrument of domination’.