The Timepiece, Metaphor and Embodiment of Modern Times

The Tyranny of Chronos explores time and the way it is depicted, addressing issues such as the link between the linear conception of time imposed by modern thinking and means of controlling productivity, together with some of the challenges and transgressions to this approach posed in non-Western cultures and in the arena of art itself. The exhibition contains over fifty items, including the latest additions to the Banco de España's portrait gallery, photographs of King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia and of the bank's former governor, Pablo Hernández de Cos by Annie Leibovitz. Alongside these artworks, a large selection of the bank's historic clocks is also on display.

Timepieces combine the artistic and the technological, the representational and the functional. They have played a crucial role in the way time has come to be perceived and represented in Western culture. As noted by Yolanda Romero, conservator at the Banco de España and curator of the exhibition, clocks are a paradigmatic embodiment of the mathematical, measurable and predictable in modern times. In her introduction to the exhibition catalogue, she writes that 'capitalist society as we know it could not have existed without a device capable of accurately measuring and commodifying time; that world is governed by its tyranny'.

The Tyranny of Chronos. View of the exhibition hall.

The Tyranny of Chronos. View of the exhibition hall.

Clocks have also occupied a central place at the Banco de España since it was first founded in the late eighteenth century by an incipient financial bourgeoisie that saw such timepieces as a symbol of progress and social distinction. Indeed, the origins of The Tyranny of Chronos lie in a research project into the bank's clock collection, which resulted in the publication of a catalogue raisonné in 2023, documenting and analysing around 150 items. The study was carried out by Amelia Aranda Huete![]() , who holds a PhD in art history from the Complutense University of Madrid and specialises in the history of clockmaking. She also worked as an advisor for this exhibition, in which more than twenty of the timepieces in our collections are on show.

, who holds a PhD in art history from the Complutense University of Madrid and specialises in the history of clockmaking. She also worked as an advisor for this exhibition, in which more than twenty of the timepieces in our collections are on show.

Some of the most important examples are described below. In addition, the exhibition catalogue (downloadable free of charge), includes texts on all the exhibits by Aranda Huete, together with an introductory essay by her on the Banco de España's collection of timepieces, which has grown up alongside the institution itself.

English bracket clock, ca. 1720. Thomas Windmills, clockmaker. From the seventeenth century on, English bracket clocks were greatly sought-after among the educated and well-off classes of Europe. According to documents in the Banco de España's Historical Archive, this clock was originally purchased for the head offices of the Banco Nacional de San Carlos – the earliest forerunner of the modern bank – on Calle de la Luna. It has a simple rectangular mahogany case, with a bell-shaped top, crowned by a pineapple. The plate and movement are visible through the glass windows on the rear and sides.

Longcase clock, ca. 1770-1780. Diego Evans, clockmaker. In 1827, this clock was listed in an inventory of furniture held at the offices of the Banco Nacional de San Carlos's payments department. It is a good example of the sort of longcase English-made clocks that proliferated from the late seventeenth century on, with the pendulum concealed inside a case that also protected the movement from dust and damage. The lacquered wood and Chinese decorations on the case are typical of English Chippendale-style longcase (grandfather) clocks. In the landscape on the front of the trunk, the cabinetmaker has sought to create a sense of depth with architecture and terraced gardens.

Mantel clock with garniture. The Four Seasons. Anonymous. In the same way as the Evans, this clock was made in the late eighteenth century, but the Banco de España did not acquire it until 1975. The case is made of porcelain and painted in pastel shades. The four seasons are represented as four full-relief children, who are also depicted on the two accompanying porcelain candelabra. The clock face in the centre of the case is surrounded by a decorated gilt bronze frame and a white imitation-porcelain enamelled chapter ring. It was made at the Sitzendorf factory in Thuringia, Germany, a heavily forested region that became one of the main centres of the European porcelain industry during this period.

Mantel clock. Allegory of Study and the Arts, ca. 1810. Anonymous. This clock was purchased by the bank in 1970 at auction from Antonio Alonso Ojeda, antique dealer, and was originally intended for the governor's office. It is an interesting example of the 'Empire' style, which covered a period from 1800 to the end of the reign of Charles X of France. Two bluing bronze figures – a young woman reading and a young man drawing – both wearing classical garb, sit on either side of the barrel housing the dial and movement. The design by Dominique Daguerre, based on statues sculpted by Louis-Simon Boizot in 1780, identifies them as allegories of Study and the Arts.

Mantel clock, ca. 1808-1838. James Moore French, clockmaker. This clock is listed in an inventory of furniture and other decorative items in the offices of Banco Español de San Fernando at 15 Calle Atocha. Born in Ireland, J. M. French made clocks, watches and chronometers and was in business between 1808 and 1842. The mahogany case takes the form of a pedestal resting on four small, gilded bronze lion-claw legs. This in turn supports, on a twin volute, a barrel housing the movement and the face, protected by a glass door with a gilded metal key.

Mantel clock, ca. 1850-1860. Joseph de Hoffmeyer, clockmaker. This was one of the first Spanish-made clocks to include a perpetual calendar, in imitation of those made by the Brocot family in the mid-nineteenth century. It was made by José de Hoffmeyer y Jiménez, the official clockmaker to Queen Isabella II of Spain. The case is in black marble. It is straight-edged and sits on a rectangular base. The front contains three white enamel dials surrounded by gilded metal bezels. The main dial, at the top is flanked by two thermometers, dated Paris 1838; the two secondary dials consist of a perpetual calendar (showing the months of the year) and a barometer.

Mantel clock with garniture, ca. 1860. Peña y Sobrino, clockmaker. This Louis XV-style clock is a copy of a design by Louis-Achille Brocot, a member of one of the most influential clockmaking families of the nineteenth century. The Brocots combined a fondness for innovation with sound commercial sense, creating an internationally successful brand that was widely imitated. The gilded bronze case is decorated with two full-relief figures of cherubs, who are holding aloft an ovaloid containing the clock dials and movements. The garniture comprises two four-armed gilded bronze candelabras, with cherubs on the shafts similar to those on the case. The face and back plate bear the signature of Spanish clockmaker Peña y Sobrino.

Longcase regulator, ca. 1880. Maple & Co., retailer. This clock, now located in the Banco de España's boardroom, features in Leibovitz's photograph of Pablo Hernández de Cos, governor of the bank from 2018 to 2024. The gilded brass dial with silver chapter ring is located at the top of the mahogany case. The hood has a moulded semicircular arch. The glazed door in the trunk, flanked by columns, affords a view of the three weights, the pendulum and the eight chiming tubes. The clock was made by Maple & Co., a London furniture store that grew to be one of the largest in the world in the late nineteenth century.

Mantel clock. Birth of a French Prince, c. 1886. Anonymous. Inspired by rococo models made during the reign of King Louis XIV of France, the main feature on the case is the god Apollo or Helios. There are also three female figures in classical garb seated on either side of a child (Cupid) who is sitting on the ground and four putti or cherubs symbolising the seasons of the year. The clock face at the top is incorporated into a blue enamelled globe, with the continent names in French. The whole sits on a base, with the coat-of-arms of the French noble family Séguier-Kerret in the middle.

Wall-mounted regulator with calendar dial, ca. 1930-1940. Carisio Anzola, clockmaker and retailer. Sold by Swiss clockmaker Carisio Anzola, who had premises at Calle Sierpes in Seville, this is a regulator with perpetual calendar patented by the Ithaca factory in New York. It has a straight wooden case, surmounted by an openwork triangular moulding. The main face is in white enamel with the hours painted in black Roman numerals. The secondary face, a 31-day calendar in Arabic numerals, has two rectangular windows displaying the weekdays and months. The pendulum is visible through the glazed door protecting the movement.

Electric wall clock, ca. 1950. Inducta, trademark. This electric clock was made in 1907 by the Swiss manufacturer Martin Fischer, who named it Magneta. Rather than using external batteries, it has a magneto generator that produces the power it needs to operate. In 1929 the patent was bought by Landis & Gyr, who marketed it under the name Inducta. The mahogany wood case has a glass door showing the movement and face. The face is in black enamelled metal and has a subsidiary dial for the seconds. It has white enamelled metal hands.

Wall and mantel clock with digital flip display, ca. 1960. Anonymous. This is the Spanish version of a functional-looking clock made by the Solari firm in the early 1960s. Brothers Nani and Gino Valle's simple straight-lined design made it ideal for showing time in workplaces and public spaces. Indeed, it was the forerunner of the rotating letter and number displays still used in stations and airports around the world. Many of these clocks were manufactured and marketed by Unión Relojera Suiza, founded in Spain in 1923.

As well as the clocks from the Banco de España Collection actually on show in the Tyranny of Chronos exhibition, another three feature in photographs by artists Manuel Laguillo and Candida Höffer. They show the pivotal role that clocks – metaphors of regulation and order – continue to have in the bank's daily life, not just as a collector's item, but also as an integral feature of the institution's buildings and workplaces.

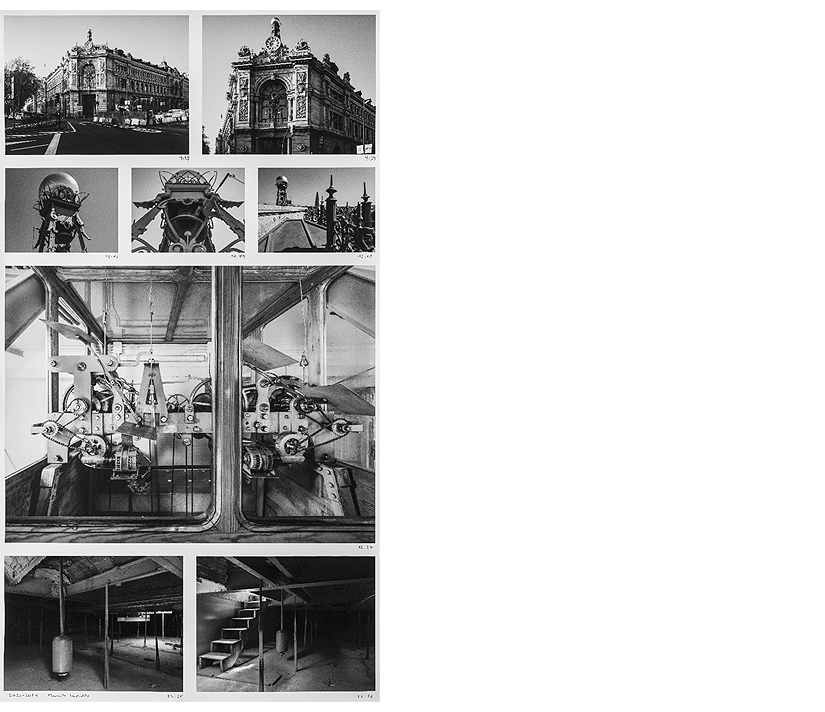

The turret clock, made by British clockmaker David Glasgow, has topped the corner section of our offices on Plaza Cibeles since 1891. Laguillo, one of the main exponents of the renewal of architectural urban photography in Spain, depicts the clock in his series Making Time Visible which takes a slow approach from outside in, almost like a time sequence, with a frisson of suspense.

German photographer Candida Höffer depicted the monumental art-deco clock that dominates the centre of the lobby of the trading floor of the Banco de España and the oeil-de-boeuf clock on one wall of the courtyard of the Main Banking Hall, (now the Library), in her series Banco de España Madrid 2000. The former is roughly 6.5 metres in height and takes the form of a rectangular column, with clock faces at the top on each side. The latter was commissioned in 1891 from clockmaker Ramón Garín, the Madrid representative of clockmaker David Glasgow. A "pendule borne" mantel clock in the exhibition is also attributed to Garín.