The Turret Clock on the Corner of Plaza Cibeles: Telling the official time at the Banco de España since 1891

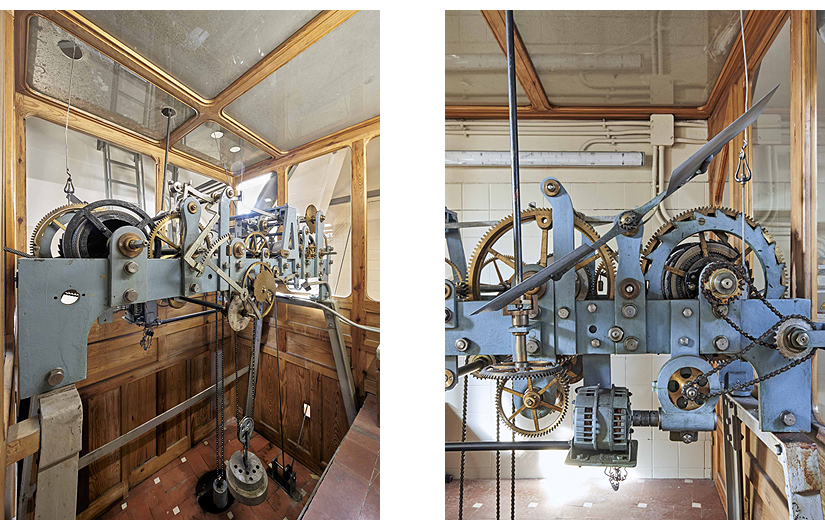

Installed over 130 years ago, the turret clock that tops the corner of our headquarters building on Plaza Cibeles is part of the visual memory of everyone who lives in and visits the city of Madrid. Its chimes feature three bells (weighing 750, 300 and 75 kg), an eight-day bronze and steel movement and a bimetal gridiron pendulum with a two-second swing. The contest for the contract to supply the clock was won by British clockmaker David Glasgow, beating four other major European firms - Ungerer Frères from Germany, Chateau Pere et Fils and Paul Garnier from France and Madrid-based Alberto Maurer.

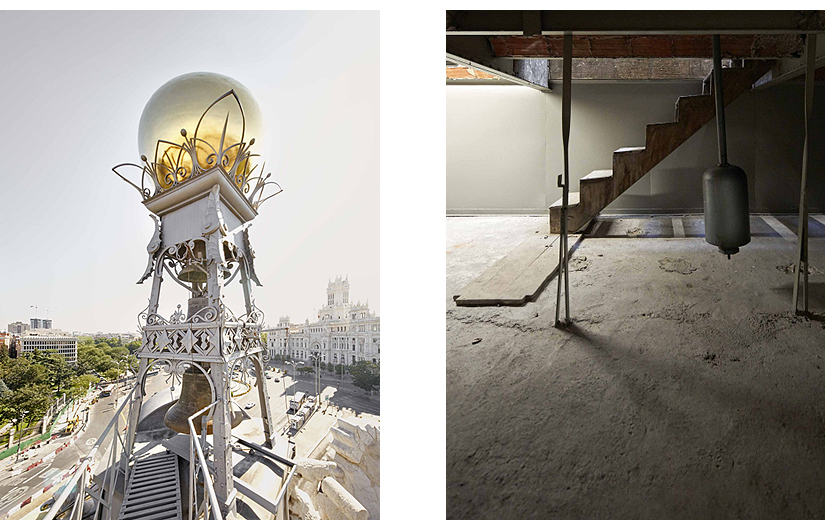

In the Catalogue of Timepieces of the Banco de España, which was publicly unveiled on 20 April last, Amelia Aranda Huete, who is the curator of timepieces and automata for Patrimonio Nacional [the National Heritage Association] and holds a PhD in Art History from the Complutense University in Madrid, explains that in mid 1889 the Works Committee of the Banco de España decided to acquire a clock for the turret of the building that the bank was then completing on Plaza de Cibeles. With its bold, elegant blend of the industrial and representative roles that comprised its two main inherent features, the building was to become one of the jewels in the crown of Spanish 19th century architecture. Indeed, in 1999 it was awarded Historical Monument status as a Site of Cultural Interest.

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Corner of Banco de España headquarters building on Plaza Cibeles

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Corner of Banco de España headquarters building on Plaza Cibeles

Curiously, one of the reasons why it was acquired was to provide a public clock that could be used as a reference for calling to order the Banco de España's general meetings of shareholders. At the time, there was no clock in Madrid by which the "official" time of day was gauged. Shareholders thus relied on the clocks of nearby town halls and parish churches, which were often quite inaccurate. This meant that some regularly arrived early and others late for meetings. This problem was solved by David Glasgow's clock, which has been telling the official time of all the bank's operations and activities since its installation in 1891.

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Bells & pendulum

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Bells & pendulum

This goal of standardisation also played a part in the bank's determination that all the clocks in its new headquarters should be connected electrically to ensure that they would be consistent with one another. They asked Glasgow to make the corner turret clock the master unit from which the rest would be regulated. Aranda Huete writes that the British clockmaker thus undertook to incorporate all the latest technological advances of his day to produce a clock that would be exceptionally accurate. The frame was to be solid cast iron, with the three main wheels made of gunmetal and the pendulum temperature-compensated using zinc and iron tubes. This would ensure that the clock was impervious to 'wind, snow and the vibrations from passing carriages', and that it would be accurate to within 4 or 5 seconds a week. It met these expectations almost exactly. Only once in its 130-year history —during the exceptionally severe Storm Filomena in January 2021![]() — have its hands stopped moving, and even then it was for only one day.

— have its hands stopped moving, and even then it was for only one day.

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Mechanism

Turret Clock by David Glasgow. Mechanism

The clock cost £386, which worked out at 9650 pesetas at the exchange rate of the time. This price included the cost of the three bells but not their transportation (first by sea from London to the port of Santander and then on to Madrid by rail), customs duty or the construction of the bell tower. Nor did it cover the cost of erecting the bells and the clock itself. The first of these tasks was handled by lead worker and mechanical constructor Luis Loubinoix and the second by clockmaker Ramón Garín, Glasgow's agent in Madrid, who was also engaged to maintain the clock. Our collection also contains two further timepieces by Garín: the oeuil de boef [or 'bullseye'] clock in the Main Banking Hall (now the library) and a table clock of a kind known as pendule borne, with Paris type French mechanism and a rectangular black marble case.

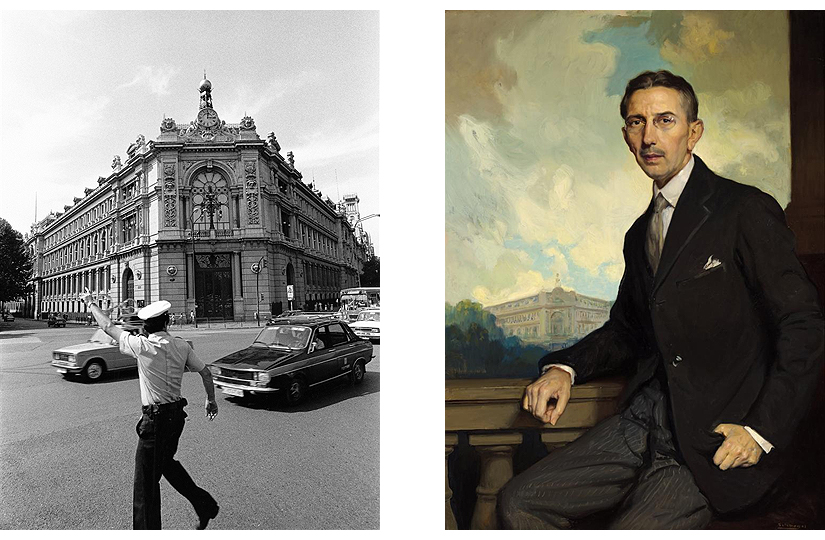

Javier Campano: Banco de España Series (1981-2001) | Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor: [Portrait of] Juan Antonio Gamazo Abarca, Count of Gamazo (1930)

Javier Campano: Banco de España Series (1981-2001) | Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor: [Portrait of] Juan Antonio Gamazo Abarca, Count of Gamazo (1930)

As time passed, the turret clock by David Glasgow became one of the most iconic features not just of the Banco de España headquarters building but of the whole Plaza de Cibeles square. Of the great many photographs of it, those taken by Javier Campano as part of his Banco de España Series (1981-2001) stand out. This series comprises over 150 photos in which, as Carlos Martín writes, Campano seeks to 'direct the eye towards the weight of history and the images sum up the protocol-focused, representative role' of the bank. More than 5 years earlier, Galicia-born painter Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor also showed Glasgow's clock in his portrait of then governor of the bank Juan Antonio Gamazo Abarca, Count of Gamazo. In a contrived but plausible composition, the governor is shown leaning on a balustrade with the trees of Paseo del Prado and the Banco de España headquarters in the background. In his essay The Hours in Numbers Garbed in the Catalogue of Timepieces of the Banco de España, Justo Navarro describes 'its gold dial looking up towards heaven' in this painting, in which the turret clock 'seems to gaze at the artist who is painting it', projecting onto this passing moment 'a halo of wisdom and permanence that symbolises the virtues of the bank'.