Banco de España Publishes Catalogue Raisonné of Timepiece Collection

Clocks have always formed part of the history of the Banco de España. The records in our archives and the investigations conducted by historian Amelia Aranda Huete show that in 1793, the Banco Nacional de San Carlos (considered to be the earliest forerunner of the Banco de España) purchased a bracket-type clock, the dial of which was signed by Thomas Windmills, for its offices on Calle de la Luna in Madrid. In one of the halls in the same building there was also a longcase clock by British clockmaker Diego Evans.

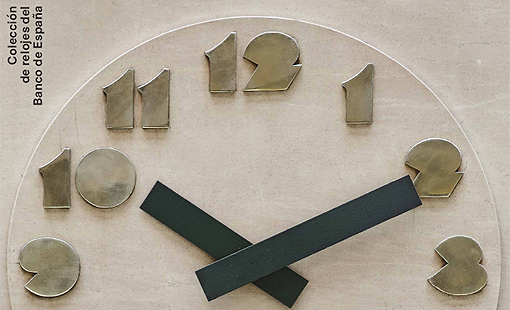

With their blend of craft and art, these devices have accompanied staff and visitors to the bank ever since. They include not only wall clocks in the offices and halls but also architectural-scale clocks presiding over the bank's buildings and its centres of financial business, such as the trading floor. Thus, over its more than 200 years of history, the Bank has built up an extraordinary collection of timepieces, which have now been compiled and analysed in a catalogue raisonné of almost 400 pages in length.

Cover of the Catalogue Raisonné of Timepieces in the Banco de España Collection

Cover of the Catalogue Raisonné of Timepieces in the Banco de España Collection

This catalogue is available in pdf format (44Mb)![]() to download free from the Publications section of our website. It contains a selection of 143 of the most valuable and representative items in the collection. Longcase clocks, wall clocks, architectural clocks, artistic and functional clocks, table and mantel clocks are grouped into three sections —'Historical Timepieces’, ‘Functional Timepieces’ and ‘Architectural Timepieces’ — accompanied by detailed fact sheets indicating who made them, where and when, what techniques were used, their measurements and other relevant details, including a specific commentary on each one.

to download free from the Publications section of our website. It contains a selection of 143 of the most valuable and representative items in the collection. Longcase clocks, wall clocks, architectural clocks, artistic and functional clocks, table and mantel clocks are grouped into three sections —'Historical Timepieces’, ‘Functional Timepieces’ and ‘Architectural Timepieces’ — accompanied by detailed fact sheets indicating who made them, where and when, what techniques were used, their measurements and other relevant details, including a specific commentary on each one.

English bracket clock, c. 1720 (Thomas Windmills, clockmaker) | Longcase clock, c. 1770-1780 (Diego Evans, clockmaker)

English bracket clock, c. 1720 (Thomas Windmills, clockmaker) | Longcase clock, c. 1770-1780 (Diego Evans, clockmaker)

This catalogue is the result of a process of study and research into the Banco de España’s clocks begun by our Curators Division in 2019. That study analysed their state of conservation, scientifically catalogued the different pieces, restored some and made detailed photographic records of them all. It was conducted by a large, multi-disciplinary team including expert clock curators, documentalists, restorers and photographers. This is the first in a number of initiatives which will be set in motion by the Bank in the coming years to investigate, catalogue and disseminate its valuable but largely unknown collections in the field of decorative arts. One of the main reasons why what is now the Banco de España Collection was set up was to obtain decorative and art objects to enhance workspaces and set off the architecture of the Bank at its central headquarters and branch offices. Those pieces have played an essential role in fulfilling that aspiration.

Table clock. Birth of a French Prince, c. 1886 (Anon.) | Table clock. Allegory of Study and the Arts, c. 1810-1820 (Anon.)

Table clock. Birth of a French Prince, c. 1886 (Anon.) | Table clock. Allegory of Study and the Arts, c. 1810-1820 (Anon.)

Timepieces in particular have been acquired and used systematically at the bank from the earliest days right up to the present. These acquisitions have been made for functional reasons, but they also have a great deal of symbolic significance. As Banco de España Curator Yolanda Romero notes in her foreword to the catalogue, the complex gears of clocks, as objects created out of the efforts of human beings to trap and represent time, become a ‘metaphor for productivity, work, order and rigour’, in line with the ‘unifying and regulatory function’ that constitutes the basic remit of the bank. In this regard, Romero writes that the most famous of all the clocks in in the catalogue, the ‘Turret Clock’ a top the bank’s headquarters on the corner of Plaza Cibeles, was installed with the deliberate purpose of providing a nearby public clock that could be used as a reference for starting meetings of the Bank's general meeting of shareholders.

Table clock, c. 1808-1838 (James Moore French, clockmaker) | Table clock, c. 1850-1860 (José de Hoffmeyer, clockmaker)

Table clock, c. 1808-1838 (James Moore French, clockmaker) | Table clock, c. 1850-1860 (José de Hoffmeyer, clockmaker)

Over and above their functional nature and their symbolic connotations, many of the timepieces in the Banco de España Collection are undoubtedly outstanding pieces of art. They reflect the tastes and interests of different eras: from the sumptuousness of the Baroque period through the serene figures of the Empire style, the melancholy of the Neo-Classical and the cold, streamlined elegance of industrial design to the evocative sobriety of Art Déco. These clocks, which were produced by different schools and artistic tendencies over the past few centuries, bear witness to the time that has passed over the bank’s long history and are key to understanding how it has changed over the years.

The ‘classical’ section of the timepiece collection comprises over 100 pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries and the first half of the 20th, produced by Europe's leading schools of clock-making. Many of them were acquired in the 1970s, but a significant number (such as those mentioned above by Windmills and Evans and two valuable clocks bearing the signatures of José de Hoffmeyer and James Moore French, respectively) were brought into the collection in the mid-19th century, according to the documentation held in the bank’s historical archives. Special mention must be made of the bank's 'architectural clocks', such as the aforementioned tower clock on the corner of Plaza Cibeles and the 'Monumental Clock' in the art déco style that has occupied the centre of the hall on the trading floor of the headquarters building since the first extension work in the 1930s. Along with these historical pieces, the items selected for the catalogue also include a number of clocks dating from the second half of the 20th century that can be considered as unique pieces in the history of industrial design.

Wall clock, second half of the 20th century (Anon.) | Digital flip wall and table clock, c. 1960 (Anon.)

Wall clock, second half of the 20th century (Anon.) | Digital flip wall and table clock, c. 1960 (Anon.)

As mentioned above, the catalogue provides detailed documentation on over 140 timepieces in the form of illustrated fact sheets with high-resolution images and explanations outlining their historical and aesthetic value. The photos are by Fernando Maquieira and the texts by Amelia Aranda Huete, who holds a PhD in History of Art from the Complutense University in Madrid![]() and is the curator in charge of clocks and automata at Patrimonio Nacional

and is the curator in charge of clocks and automata at Patrimonio Nacional![]() [Spain's National Heritage association]. She has also written an extensive essay introducing the history, characteristics and unique features of our collection of timepieces.

[Spain's National Heritage association]. She has also written an extensive essay introducing the history, characteristics and unique features of our collection of timepieces.

Journalist and writer Justo Navarro also contributed an essay entitled Las horas ya de números vestidas [TN1] ['The Hours in Numbers Garbed'], in which he analyses and highlights the crucial role played by clocks as instruments per se but also as motifs and objects in numerous art works, given their ornamental value and their innumerable symbolic and philosophical connotations, in the history of art and especially in shaping our heritage collection. Before the two essays there is a welcome message from Pablo Hernández de Cos, Governor of the Banco de España, and a general foreword by Yolanda Romero, the bank's curator. As an aid to understanding, the catalogue also includes a glossary of clock-making terms and short biographies of the makers of the most outstanding pieces in the collection.

Tower & belfry clock, c. 1890 (David Glasgow, clockmaker) | Circular wall clock, c. 1891 (Ramón Garín, clockmaker)

Tower & belfry clock, c. 1890 (David Glasgow, clockmaker) | Circular wall clock, c. 1891 (Ramón Garín, clockmaker)