Decolonising clock time

The Tyranny of Chronos explores time and the ways in which it is depicted. The exhibition shows that there are ways of conceiving, experiencing and representing time that go beyond the linear conception imposed by modern thinking. The third section of the show, entitled Unclocked Time, includes works by Guatemalan artists Antonio Pichillá, Ángel Poyón Cali and Manuel Chavajay. In their own way, each of these artists highlights the non-utilitarian, cyclical view of time, linked to earth and nature, that still survives in some non-Western cultural contexts. All three artists explore this concept from an entirely contemporary perspective.

Antonio Pichillá (b. San Pedro de la Laguna, Guatemala, 1982), is a Tz'utujil Mayan artist who lives and works in his home town on the shores of Lake Atitlán. Two of his works are on show here: Kukulkan (the Feathered Serpent) (2017) and Seed (2024). The first is a colourful snake-shaped piece of sculpture made from mahogany and yarn. According to María Jacinta Xón Riquiac, it is a reinterpretation of the ancestral technology of the q’inb’al (warping board). For the indigenous peoples of Abya Yala, the Kukulkan or Serpent Bird is a 'being of diverse life that watches over time, space, water, and rain'. Used as a 'contemporary conceptual object,' Xón Riquia explains, the snake becomes a warp that invokes a history of resistance and, at the same time, a 'metaphor for memory and knowledge that for Pichillá represents the continuity of his relationship with his weaver grandmother and the legacy she handed down to her descendants'.

Antonio Pichillá: Kukulkan (The Feathered Serpent) (2017)

Antonio Pichillá: Kukulkan (The Feathered Serpent) (2017)

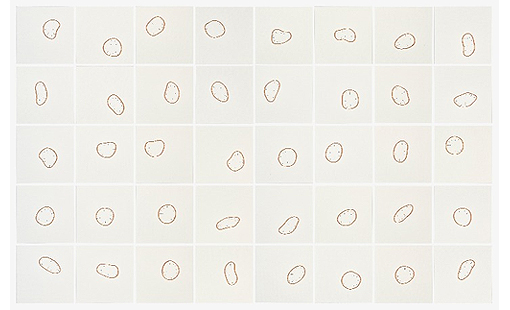

The other piece in the exhibition by Pichill is Seed (2024), a textile piece that references the key place given in Tz'utujil Mayan culture to crop planting, a practice that is closely associated with reproduction. The work warns that this custom may soon be lost as a result of the 'civilising' process that alienates humans from any direct relationship with the cultivation of the land. 'Planting, like weaving, is intrinsic to time', writes the artist. Humanity must understand that it too is a form of 'sowing', something that must be 'cared for, cleaned and fertilised'. We need to view 'our existence as a symbiosis with the sun, air, water, dreams, and earth'. This is the only way of ensuring our long-term survival.

Antonio Pichillá: Seed (2024)

Antonio Pichillá: Seed (2024)

The exhibition also includes two pieces by Ángel Poyón Cali (b. San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala, 1976). As Xón Riquia writes, Povón challenges the 'the positivist linearity of modernity with the multidimensionality and diffraction of ideas, narratives, and meanings in Kaqchikel Maya daily life'. The first of the two works is Imagined Place No. 2 (2022), which depicts a clock face without hands across which flies a flock of migratory raptors (azacuanes). The spherical clock frame alludes to the modern perspective of quantified, self-enclosed, time. At the same time, it also references that other limit set by the imperial-capitalist order, the national border, which restricts movement or imposes a legality on it that perpetuates the privilege of the dominant classes and the colonisers. By contrast, the flight of the birds reminds us that, paralleling the 'obsessive measurement of modern time', the 'time of nature' continues its course. Colonisation has deprived the original Meso-American peoples of this non-mechanised time and of free access to the fruits they obtained from their symbiotic relationship with the land. What it has been unable to take from them, the artist is saying, are their dreams.

Ángel Poyón Cali: Imagined Place No. 2 (2022)

Ángel Poyón Cali: Imagined Place No. 2 (2022)

The other piece by Ángel Poyón Cali is The Present is Ours No. 4 (2018). With its drawings of clocks with undefined edges, 'a little round, a little square', it takes us back to our infancy and the child's natural resistance to the imprisonment and quantification of time. It also alludes to the more open and flexible relationship that the Kaqchikel communities enjoyed with time until just a few decades ago, when their lives and work were not conditioned by clocks and they had 'quotidian rituals, not survival routines, in their daily lives'. This idea of time as something flexible and multiform – reinforced by the rubber used in the piece – highlights the fact that although its existence is constant, the ways of living it are 'infinitely unpredictable'.

Ángel Poyón Cali: The Present is Ours No. 4 ( 2018)

Ángel Poyón Cali: The Present is Ours No. 4 ( 2018)

Through his work, Manuel Chavajay (b. San Pedro de la Laguna, Guatemala, 1982) wants to contribute to preserving and showcasing the sacred landscapes and traditions that define the Tz'utujil Mayan legacy. The work on show here, Untitled (2023), is a drawing of almost abstract texture from his series K'o q'iij ne t'i'lto' ja juyu' t'aq'aaj. Chavajay depicts a road running through a landscape of 'mountains sacrificed to make human life faster' on Lake Atitlán, at an unspecified time of day, perhaps before dawn or just after sunset. The upper part of the canvas is covered in black flows of burnt oil, like furtive brushstrokes alluding to the slow but inexorable impact of pollution on this territory. The centre of the painting is taken up by the 'Grandmother Moon', embroidered on cotton paper. As in his other works, the full roundness of the moon is incomplete. 'The moon,' Chavajay reminds us, 'is always there, but we only see it partially, or not at all. Observing it unhurriedly, without the need for any instruments ( (‘our eyes’ he says ‘have a capacity that no camera can imitate’), we can better understand the 'rhythm of nature'.

Manuel Chavajay: Untitled. From the series K'o q'iij ne t'i'lto' ja juyu' t'aq'aaj (2023)

Manuel Chavajay: Untitled. From the series K'o q'iij ne t'i'lto' ja juyu' t'aq'aaj (2023)