What a strange vanity painting is; it attracts admiration by resembling the original we do not admire

The exhibition Flowers and Fruit, which is on show until 25 February at the exhibition hall at the Banco de España headquarters building on Plaza Cibeles, is the starting point for the latest instalment of the 'Itineraries' section of the website, in which external authors (historians, writers and artists) are invited to take a personal journey through our collection. On this occasion the guest author is Carmen Ripollés, who teaches at the Art Department of Portland State University. Her main research lines include the historical analysis of the still life genre, the links between art and science and the notions of artistic identity and material culture.

The title of her itinerary is Flowers (and Fruits) from Other Worlds. It begins with a quote from philosopher Blaise Pascal that highlights the paradox that has always affected art genres which depict fruit, flowers and other inanimate objects: ‘What a strange vanity painting is; it attracts admiration by resembling the original we do not admire’ (Pensées, 1660). Artists from different regions and periods working in a vast variety of media, she writes, have transformed the apparently insignificant and innocuous subject of flowers and fruit into an object of admiration, sensory pleasure and profound reflection. As a result, and as the title of the itinerary suggests, 'flowers and fruits from other worlds' have appeared. In some cases the desire to mimic transcends the reality of the subject depicted and in others there are quite literally ‘other’ worlds, containing imagined, invented or remote plants.

Juan van der Hamen: Pomona and Vertumnus (1626) | Juan de Arellano:Vase (c.1668)

Juan van der Hamen: Pomona and Vertumnus (1626) | Juan de Arellano:Vase (c.1668)

The first block of works selected for the itinerary comprises five pieces from our Classical Collection which Carmen Ripollés believes should be visualised as hanging in a palatial home in 17th century Madrid: a mansion such as that of Jean de Croÿ, Second Count of Solre, where two canvases by Juan van der Hamen selected by Ripollés (Pomona and Vertumnus (1626) and Still Life with Fruit and Sweetmeats (c. 1621)) actually hung. Two more of the works in this first block —the tapestry March and April (Gerard Peemans, c. 1679) and the oil painting Vase (Juan de Arellano, c. 1668)— evidence the growing interest that emerged during the Baroque period in the theme of flowers, due to their strange similarity to objects manufactured by human intervention.

The use of this motif to spark reflections on where the limit between the real and the artificial lies can also be seen in the next three pieces in the itinerary: Busan02, from the series Artificial Paradises (Paula Anta, 2008), Art Forms in Mechanism XXVI (Linarejos Moreno, 2016-2022) and Pink Lotus (Felicidad Moreno, 2021). All three are by female artists, as is Portrait of Señora Cañas (1950) by Georgian-born artist Olga Sacharoff. The first two are photos; photography has played an essential role in updating the still life genre. The other two are paintings, each with its own assumptions from the relevant historical context, which convey a message of feminist empowerment by reinterpreting the connection between flowers and the ornamental and feminine.

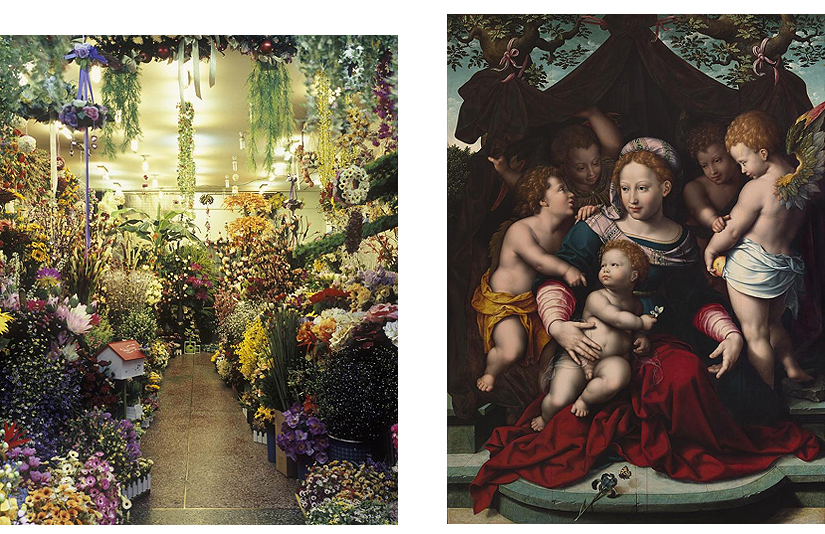

Paula Anta: Busan02 from the series Artificial Paradises (2008) | Cornelis van Cleve:Virgin of the Lily (c. 1550)

Paula Anta: Busan02 from the series Artificial Paradises (2008) | Cornelis van Cleve:Virgin of the Lily (c. 1550)

At this point in her itinerary, Carmen Ripollés jumps back in time to one of the oldest works in our Collection: Madonna of the Lily (Cornelis van Cleve, c. 1550). She describes this painting as a marvellous example of the 'prehistory' of still life (which is perhaps the first genre in which painting itself became a core concern), with the lily portrayed as a trompe l'oeil, precariously balanced on the edge of the step. This lily is also laden with symbolism, as it alludes to the Passion of Christ, which Ripollés believes connects it to vanitas, a sub-genre of still life that addresses the fleeting nature of life and the impossibility of dodging the effects of the passage and weight of time.

Pancho Cossío:Still Life with Ace of Clubs (1955) | Mireya Masó:Untitled (2001)

Pancho Cossío:Still Life with Ace of Clubs (1955) | Mireya Masó:Untitled (2001)

An updating of the Baroque notion of vanitas can be seen in some of the works that follow Madonna of the Lily on the itinerary: Still Life with Ace of Clubs (Pancho Cossío, 1955), Burnt Food (Miquel Barceló, 1985), Grapes (Xavier Toubes, 1992), Bronze Dresser I (Carmen Laffón, 1995) and Untitled (Mireya Masó, 2001). Allusions to the evanescence of life can also be found in some of the works already mentioned here, such as Vase by Juan de Arellano and Pomona and Vertumnus. Ripollés states that this last painting covers many of the themes addressed in the itinerary, and for that reason she returns to it time and again in her introductory text for the website and the longer essay![]() that supplements it.

that supplements it.

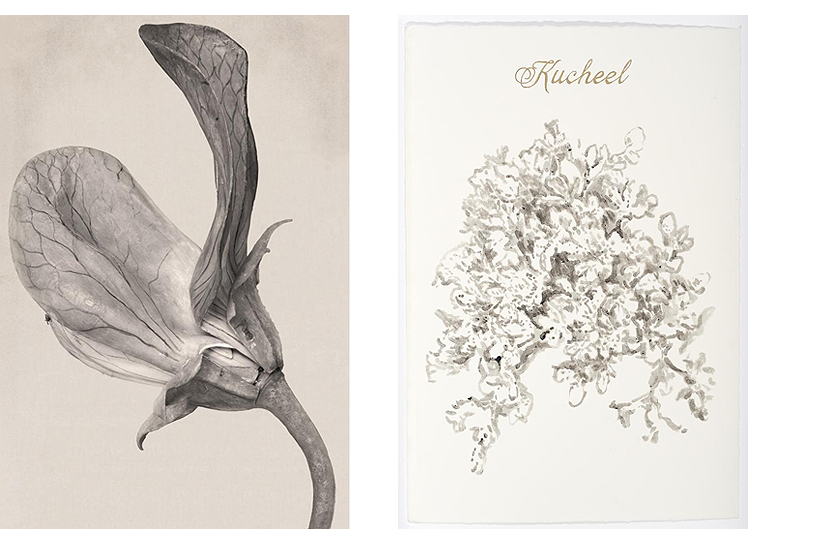

Linarejos Moreno: Art Forms in Mechanism XXVI (2016-2022) | Fritzia Irízar: Untitled (Endangered Plants from the Yucatan Jungle) ( 2020-2021)

Linarejos Moreno: Art Forms in Mechanism XXVI (2016-2022) | Fritzia Irízar: Untitled (Endangered Plants from the Yucatan Jungle) ( 2020-2021)

Blending the pictorial illusionism of vanitas with a vein of scientific classification, the great cornucopia that Juan van der Hamen shows at the feet of the goddess Pomona contains local fruits and vegetables mixed with others from the American colonies. This mix served to reinforce his praise for the generosity of nature, which provides fruit and asks nothing in return. As a product of his era and context, he followed the same colonialist logic that characterised the botanical treatises of the time. The last three works in the itinerary rebel against that logic and its devastating effects on cultural diversity and environmental sustainability: Wakari (Sweet Jungle Fruit) (Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe, 2019), Untitled (Endangered Plants from the Yucatan Jungle) (Fritzia Irízar, 2020-2021) and Brazilian Rain Forest (Peter Hutchinson, 2008).