Rogelio López Cuenca wins 2022 National Award for Plastic Arts

Rogelio López Cuenca![]() (b. Nerja, 1956) has won the National Award for Plastic Arts, awarded by the Ministry of Culture and Sport. The jury considered the career of this Malaga-born artist to be ‘essential for tracing the critical history of Spanish art from the 1980s to the present day’. They stressed the scope and depth of his artistic exploration of ‘the violence and displacement entailed by globalisation’ and the ‘silenced memories of the past’ and the way in which those ‘forced silences structure real and symbolic space in the present'. To mark López Cuenca’s receipt of the award, here is an outline of the artist’s works in our collection.

(b. Nerja, 1956) has won the National Award for Plastic Arts, awarded by the Ministry of Culture and Sport. The jury considered the career of this Malaga-born artist to be ‘essential for tracing the critical history of Spanish art from the 1980s to the present day’. They stressed the scope and depth of his artistic exploration of ‘the violence and displacement entailed by globalisation’ and the ‘silenced memories of the past’ and the way in which those ‘forced silences structure real and symbolic space in the present'. To mark López Cuenca’s receipt of the award, here is an outline of the artist’s works in our collection.

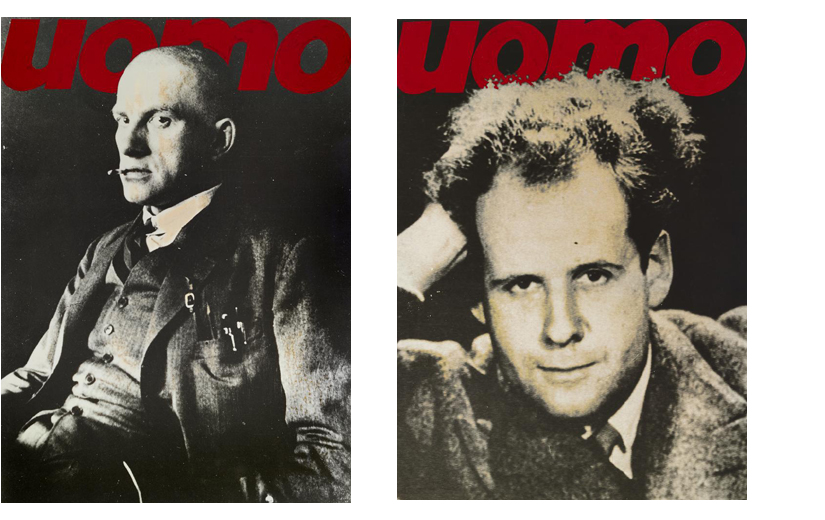

Rogelio López Cuenca: Uomo (Maiakovski) (1992) and Uomo (Eisenstein) (1992)

Rogelio López Cuenca: Uomo (Maiakovski) (1992) and Uomo (Eisenstein) (1992)

To begin, let’s look at Uomo (Maiakovski) (1992) and Uomo (Eisenstein) (1992). The first was featured in (Un)common values, a recently-closed exhibition of a selection of works from the contemporary art collections of the Banco de España and the National Bank of Belgium (NBB). The show was held in the NBB’s exhibition space at its head offices in Brussels. These two pieces are part of a series that López Cuenca produced in the early 1990s, which he based on the covers of well-known magazines associated with the consumer society. Here, his starting point is the men's magazine Uomo, the content of which leans towards the construction of a certain image of attractive, powerful, successful Western men. The artist plays with the different meanings of the word uomo. Ever since the start of his career, he has sought to explore the critical potential of the displacement of signs and an effect of strangeness. He recreates the cover of the magazine, featuring two key figures from the Soviet cultural revolution of the early 20th century: poet Vladímir Mayakovsky and pioneering film-maker Sergei M. Eisenstein.

These mock covers, like others that he created featuring painter Aleksander Rodchenko and conceptual artist Joseph Beuys, were produced at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union. His critique thus works on two levels: the more obvious involves his unmasking of the ideological nature of apparently neutral objects, such as fashion magazines, that we buy every day; the second, more subtle level alludes to the fetishistic link between petit bourgeois Western culture and certain revolutionary symbols, which undermines their transformational potential.

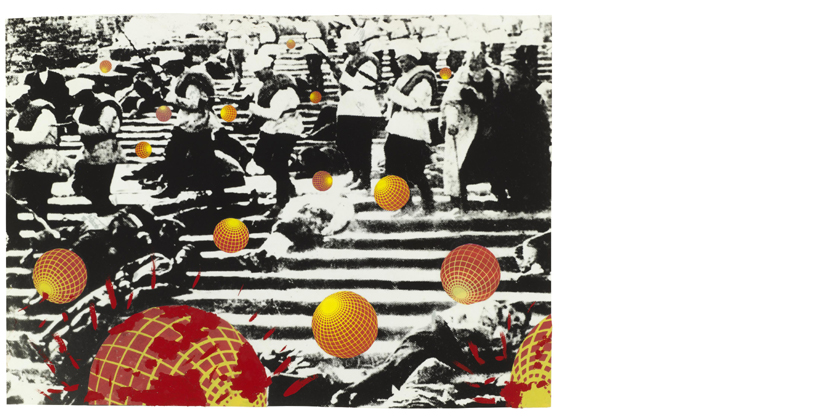

Rogelio López Cuenca: Odessa (1992)

Rogelio López Cuenca: Odessa (1992)

Soviet revolutionary imagery also features in another work by Rogelio López Cuenca in the Banco de España Collection: Odessa (also from 1992). This small collage was one of a group of works in which the artist appropriated the brand image of the Expo ’92 Universal Exhibition in Seville. The group includes his controversial (and censored) project Décret nº 1, in which he intervened in the official signs for the event. López Cuenca takes a single frame from the famous scene in Battleship Potemkin (Sergei M. Eisenstein, 1925) showing the massacre of civilians on the steps in the Ukrainian city of Odessa by the White Army of the Czarist state. Onto it he affixes a number of replicas of the armillary sphere used as the logo for Expo ’92, which become tumbling projectiles that help the soldiers in their indiscriminate charge against the protestors. Carlos Martín writes that after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the break-up of the USSR, at a time when people were talking about the 'end of history', that logo became an icon of a triumphant capitalism that was not only bulldozing the last symbolic vestiges of the Soviet revolutionary utopia on its path to constructing the new world order, but also hinted at a 'post mortem victory of the old regime decades after its fall".

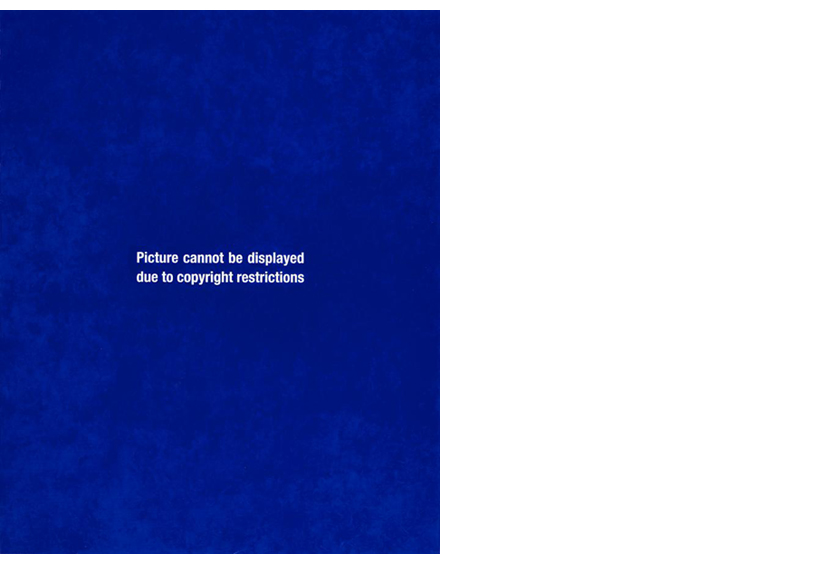

Rogelio López Cuenca: Copyright (White/Blue) (2012)

Rogelio López Cuenca: Copyright (White/Blue) (2012)

The last work featured here is the most recently acquired: Copyright (White/Blue) (2012). Against a blue background in oil paint applied with a palette knife, we see the phrase 'Picture cannot be displayed due to copyright restrictions'. López Cuenca uses a complex conceptual strategy to denounce the censoring of images for market-related reasons and the resulting speculation in regard to reproductions of works of art. This has become a core issue in his work in recent years. Using the resources and textures of conventional oil painting on canvas, he constructs a painting that denies access to the image that it should apparently contain. In the words of Carlos Martín, this reverses 'the logic of technical reproductions of art works, where we have the image (in the form of a postcard, a t-shirt or a fan) but none of the tangible value of the work'. In this way, López Cuenca, who pioneered the use of Creative Commons licences![]() in the context of Spanish art, critiques the increasing commodification of cultural products in latter-day capitalist society. That critique has formed the core of some of his most iconic recent projects, such as Picasso City

in the context of Spanish art, critiques the increasing commodification of cultural products in latter-day capitalist society. That critique has formed the core of some of his most iconic recent projects, such as Picasso City![]() , in which he highlights the way in which that commodification is linked to other processes of dispossession of common goods, such as gentrification and the promotion of large-scale tourism.

, in which he highlights the way in which that commodification is linked to other processes of dispossession of common goods, such as gentrification and the promotion of large-scale tourism.