The Banco de España inaugurates a permanent exhibition space with a show on the origins of its art collection, linked to Goya

The exhibition hall is located at the corner of its Cibeles headquarters, on Madrid's Paseo del Arte Over the coming years, it will host a series of temporary exhibitions in which the bank wants to showcase the valuable artistic and documentary legacy it has built up over its long history.

The first exhibition, 2328 reales de vellón. Goya and the Origins of the Banco de España Collection was officially opened by King Felipe VI and will be on public view until 26 February 2022.

2328 reales de vellón. Goya and the Origins of the Banco de España Collection, explores the first hundred years of the collection, from 1782 —when the Banco de San Carlos![]() was founded— to the early years of the Banco de España, which emerged under its current name in 1856, following the merger of the Banco de San Fernando

was founded— to the early years of the Banco de España, which emerged under its current name in 1856, following the merger of the Banco de San Fernando![]() and the Banco de Isabel II

and the Banco de Isabel II![]() . It also examines the way in which those early beginnings conditioned the subsequent development of the collection.

. It also examines the way in which those early beginnings conditioned the subsequent development of the collection.

This exceptional set of works, which form the core of the Banco de España's classical collection, is on public display for the first time, offering a unique insight into the origins of this Enlightenment collection, one of the most important in Spain and amongst central banks more widely.

The exhibition analyses the role played by the Banco de España's forerunners in creating the collection. As well as the magnificent set of paintings commissioned or acquired during the period, it also includes documents, books, printed matter and banknotes from the bank's historical archive and library. In addition to the portrait gallery, with paintings of the bank's managers and governors, members of the royal family and other figures linked to the bank's history, there are also items from its collection of decorative items, including clocks, furniture and silverwork.

A real de vellón was a coin valued at a quarter of a peseta and the title of the exhibition, 2328 Reales de Vellón, is a reference to the sum paid to Goya for his portrait of José de Toro-Zambrano, the first director of the Banco de San Carlos. The shrewd decision to include Goya among the artists entrusted with immortalising the bank's history launched a tradition of commissioning official portraits of leading figures with links to the institution, which has continued to the present day. As a result, the portrait gallery is now —in the words of Javier Portús— "one of the finest sets of paintings for studying the development of Spanish official portraiture in the late modern and contemporary periods".

The choice of Goya also exemplifies the support provided by the Banco de España Collection to contemporary artists from each historical period since. It was not a common policy at the time; other institutions were more inclined to acquire works by great artists of the past. The purpose of these commissions and acquisitions was not merely to preserve the institution's memory or express its gratitude to its leaders; it also formed part of an Enlightenment ideal of promoting art and a strong belief in the power of patronage as an instrument for nurturing creativity and boosting the economy.

To this end, the bank not only commissioned official portraits, but also hired artists and craftspeople from very diverse fields, including the decorative arts, banknote design, book- and document-making and architecture. Consequently, the exhibition also includes a wide variety of items from the everyday life of the bank's forerunners, ranging from decorative and representational objects to others linked to its financial activities (certificates, share certificates, official documents, reports, etc.).

Together they speak to us not only of the history of the Banco de España, but also the society of the time. For example, the clocks in the exhibition reflect a passion for timepieces among the Enlightenment élite, which received a further boost with the establishment of the Royal Clock & Watch Factory (Real Fábrica de Relojes), which operated between 1788 and 1793. The exhibition includes three examples —by Diego Evans, Thomas Windmills and José de Hoffmeyer— with their original striking mechanisms, which tolled the hours in the bank's halls and offices.

JOSEPH DE HOFFMEYER. Mantel clock, c. 1850 Black marble and gilded bronze. Provenance: Probably from the Banco Español de San Fernando. Banco de España Collection

JOSEPH DE HOFFMEYER. Mantel clock, c. 1850 Black marble and gilded bronze. Provenance: Probably from the Banco Español de San Fernando. Banco de España Collection

The exhibition is divided into two sections:

The first contains items acquired from the Banco de San Carlos![]() , and consists of portraits of its first managers and the group of Enlightenment figures who promoted its foundation, almost all by Francisco de Goya. The ten portraits by Goya shown here are essential to understanding the artist's extraordinary rise to fame in the 1780s following his arrival in Madrid and the means by which he gained admission to Enlightenment and court circles. Featured amongst these is the work generally considered to be Goya's first great court portrait, his Portrait of the Count of Floridablanca (1783), in which he masterfully employed all the allegorical elements typical of the genre. To one side of the minister, Goya has placed the drawings of the public works he instigated, representing the most technically advanced and beneficial policy of his term in office. They include the blueprints for the Imperial Canal of Aragon. On the left, Floridablanca's strong support for the arts is embodied in the figure of Goya himself.

, and consists of portraits of its first managers and the group of Enlightenment figures who promoted its foundation, almost all by Francisco de Goya. The ten portraits by Goya shown here are essential to understanding the artist's extraordinary rise to fame in the 1780s following his arrival in Madrid and the means by which he gained admission to Enlightenment and court circles. Featured amongst these is the work generally considered to be Goya's first great court portrait, his Portrait of the Count of Floridablanca (1783), in which he masterfully employed all the allegorical elements typical of the genre. To one side of the minister, Goya has placed the drawings of the public works he instigated, representing the most technically advanced and beneficial policy of his term in office. They include the blueprints for the Imperial Canal of Aragon. On the left, Floridablanca's strong support for the arts is embodied in the figure of Goya himself.

FRANCISCO DE GOYA Y LUCIENTES. José Moñino y Redondo, First Count of Floridablanca, 1783. Oil on canvas. Acquired in 1986. Banco de España Collection

FRANCISCO DE GOYA Y LUCIENTES. José Moñino y Redondo, First Count of Floridablanca, 1783. Oil on canvas. Acquired in 1986. Banco de España Collection

Other important works are the Portrait of the Count of Altamira, in which Goya demonstrates a new approach, achieving the details more abstractly with less paint, and the Portrait of Francisco de Cabarrús, the great financier and merchant, who was the ideologue behind the Banco de San Carlos. Here, the subject is depicted wearing an extraordinary outfit of green silk, a reference to his prowess in boosting the country's economy (green being a symbol of wealth). Cabarrús was a representative of the emerging haute bourgeoisie, a new social class which Goya portrayed by updating the traditional image of the powerful man, which had heretofore been exclusively confined to the aristocracy in Spain.

The exhibition also includes a small group of religious works from the Chapel in the Bank's original offices at Calle de la Luna. Tellingly, the bank's chief purpose in erecting a chapel within the bank was to maximise its employees' productivity by allowing them to fulfil their religious obligations without having to leave the building. From the Chapel comes one of the masterpieces of the collection of The Madonna of the Lily by Cornelis van Cleve.

CORNELIS VAN CLEVE. Madonna of the Lily c. 1550 Oil on panel. Acquired by the Banco Nacional de San Carlos in 1787. Banco de España Collection

CORNELIS VAN CLEVE. Madonna of the Lily c. 1550 Oil on panel. Acquired by the Banco Nacional de San Carlos in 1787. Banco de España Collection

The second section of the exhibition is given over to works that were added to the collection during the nineteenth century. They come from the Banco de San Fernando, Banco de Isabel II and the Banco de España in its early years. This section opens with a monumental portrait of Ferdinand VII, considered to be one of the masterpieces of Vicente López, in which the artist exhibits his fine draughtsmanship and his skill in reproducing textures. The portrait is also of great typological interest, as it is a rare example of a monarch being depicted in a seated position (an allusion to the king's administrative responsibilities).

VICENTE LÓPEZ PORTAÑA. Ferdinand VII, 1832 Oil on canvas. Commissioned by the Banco Nacional de San Carlos in 1828. Banco de España Collection

VICENTE LÓPEZ PORTAÑA. Ferdinand VII, 1832 Oil on canvas. Commissioned by the Banco Nacional de San Carlos in 1828. Banco de España Collection

The bank's new commissions and acquisitions of the nineteenth century centred primarily on court figures, such as the portraits of Isabella II and Ferdinand VII. Following the fall from grace of Cabarrús and his circle at the end of the eighteenth century, the custom of commissioning portraits of the institution's managers lapsed until 1852, when the Banco de San Fernando decided to commission a portrait of its governor, Ramón de Santillán, in gratitude for his reorganisation of the institution and the merger with the Banco de Isabel II. They entrusted the work to one of the most respected court painters of the time,Jose Gutierrez de la Vega.

JOSÉ GUTIÉRREZ DE LA VEGA Y BOCANEGRA. Ramón de Santillán González, 1852 Oil on canvas. Commissioned by the Banco Español de San Fernando in 1852. Banco de España Collection

JOSÉ GUTIÉRREZ DE LA VEGA Y BOCANEGRA. Ramón de Santillán González, 1852 Oil on canvas. Commissioned by the Banco Español de San Fernando in 1852. Banco de España Collection

From 1881, it was decided to have portraits made of all the bank's governors in three-quarter view, a format that has largely persisted to the present day. Among the few exceptions is the picture of Pedro de Salaverría by Federico de Madrazo, which is similar in composition to Goya's depiction of the Count of Altamira, with the sitter wearing his official costume and seated at a table. This section provides an interesting opportunity to compare two important works from Madrazo's career, painted almost forty years apart: the Portrait of the Duke of Osuna (1844), considered to be the foremost portrait of a male subject from the Spanish Romantic school, and his portrait of Salaverría (1881), which concludes the exhibition.

FEDERICO DE MADRAZO Y KUNTZ. Pedro Salaverría, c. 1881 Oil on canvas. Commissioned in 1877. Banco de España Collection

FEDERICO DE MADRAZO Y KUNTZ. Pedro Salaverría, c. 1881 Oil on canvas. Commissioned in 1877. Banco de España Collection

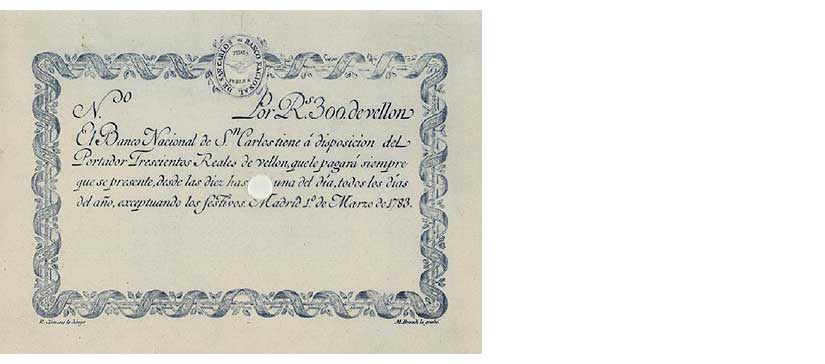

The exhibition also includes a special section with share certificates, banknotes, publications and other securities issued by the bank. These pieces are not only a reflection of the institution's financial and administrative activity, but also demonstrate the great importance given to such items and the resulting support provided to the graphic arts. The Banco de San Carlos undertook meticulous work in both of these areas, applying it in the bank notes it issued with intaglio engravings.

On display are some of the first banknotes ever issued in Spain: the Banco de San Carlos "cédulas" printed on paper of different colours, with some magnificent watermarks and motifs, created by leading artists and engravers of the time. The Banco de San Fernando and Banco de Isabel II continued this tradition, incorporating new more economical techniques such as lithography, which also offered improved security. Despite the clearly utilitarian function of these items, there was still room for artists to display their talents, incorporating decorative motifs and symbolic references (the god Mercury and his symbols, cornucopias, merchant ships, etc.) in reference to the business and industry the bank promoted.

First Spanish banknotes: Banco de San Carlos cédulas. Banknote worth 300 reales de vellón. 1 March 1783. Original: intaglio on copper. Drawing by Rafael Ximeno. Engraving by Mariano Brandi. Archivo Histórico Banco de España, c. 1782

First Spanish banknotes: Banco de San Carlos cédulas. Banknote worth 300 reales de vellón. 1 March 1783. Original: intaglio on copper. Drawing by Rafael Ximeno. Engraving by Mariano Brandi. Archivo Histórico Banco de España, c. 1782

This exhibition marks the conclusion of two years of intense work by the Banco de España to showcase its rich and varied artistic collection. Other features of the project include the recent publication of the three-volume catalogue raisonné of the Banco de España Collection and the creation of this web portal. In addition, with the renovation and opening of the Chaflán-Cibeles Hall, the bank has recovered one of the most representative historical entrances to the building for public use. In 1999, the building was declared a Site of Cultural Interest, in the Historical Monuments category.

CATALOGUE

A catalogue has been published to go with the exhibition. As well as featuring the works on display, with comments and research from eighteen specialists, it also includes texts by the curators and essays by other authors (Ismael Amaro, Carlos G. Navarro, María de Inclán, Pablo Marin Aceña, Joaquin Selgas and Elena Serrano).