'Highlights' section updated with work by Natividad Bermejo, Rosa Brun and Magdalena Correa

The Highlights section of our website regularly turns the spotlight on three pieces from the collection which we feel merit particular attention. For our latest update, we have chosen three works dating from between 1995 and 2016: Eclipse, a drawing by Natividad Bermejo (b. Logroño, 1961), Dextro, a painting by Rosa Brun (b. Madrid, 1955) and La Rinconada, a photographic series by Magdalena Correa (b. Santiago (Chile), 1968). The three pieces demonstrate the quality and diversity of contemporary art in the Banco de España's collection (around eighty percent of the total), and the large number of women artists in this section.

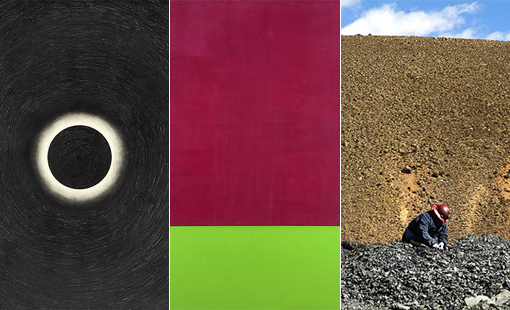

Natividad Bermejo: Eclipse (1995)

Natividad Bermejo: Eclipse (1995)

The earliest of the pieces in this selection is Eclipse (1995), made during a period when Natividad Bermejo was beginning to focus on drawing, having previously worked mainly with sculpture, installation, video and photography. Bermejo uses different scales of grey in her painting, employing techniques such as oil, charcoal and graphite, to create an austere plastic vocabulary with an unmistakable poetic force that organically combines the 'hyperreal and the dreamlike', as Roberto Díaz has noted. She reduces the motifs to a minimal gesture, and they stand out like figures emerging from the darkness of the surface. Beatriz Herráez describes the result as a 'thought-provoking range of nocturnal scenes (...) capable of engendering disquieting atmospheres and perturbing the viewer'. Herráez argues that Bermejo's work forms part of a deep-rooted tradition that aspires to strip out 'any form of ornamentation to concentrate on a rigorous analysis of forms'. This enables her to metaphorically expand the object or scene represented, as we see not only in Eclipse, but also in her other two drawings in the collection, Untitled (1998) and Untitled (2000).

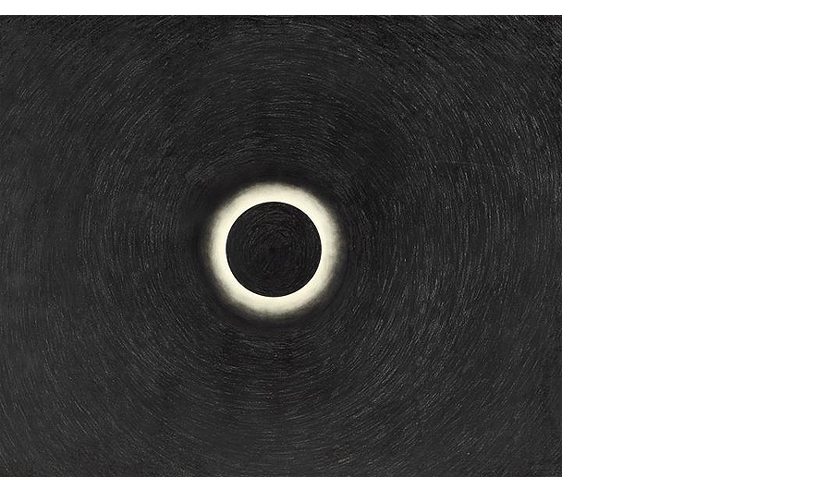

Rosa Brun: Dextro (2003)

Rosa Brun: Dextro (2003)

The second in of our featured paintings is Dextro (2003), by Rosa Brun, an artist who has undertaken a radical search for the limits of the pictorial. She employs simple geometric shapes on flat fields of colour, in strong, contrasting acidic tones, applied to aluminium or wood to bring a certain expressive quality to the paint. Her paintings challenge the viewer's perception, creating what Roberto Díaz calls, 'opposing sensations: balance/chaos, hot/cold, heavy/light, empty/full, vertical/horizontal'. In the case of Dextro, she disturbs the two-dimensionality of the picture by means of a complex relationship between the two fields of colour; the upper one is raised above the lower to create a false perspective that generates a sense of alienation. According to Carlos Martín, de Brun offers an updated and developed version of the geometrical abstraction of early avant-garde artists, focusing on the problem of perception and posing the need to critically reinterpret the exhibition itself as a 'delimited and conditioned space'. In Spanish, the dextro was the area on church grounds where sanctuary and other privileges could be claimed. In other words, it is an enclosed and protected space which – like that which has grown up around painting and sculpture – is governed by rules that differ from those of the outside world.

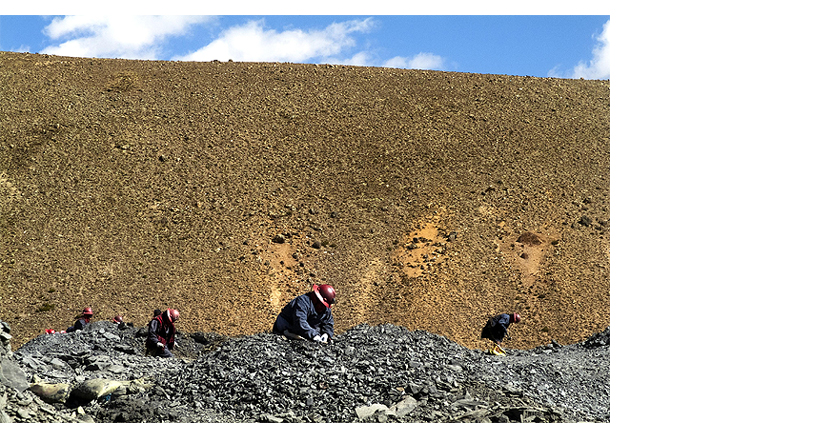

Magdalena Correa: La Rinconada (2012-2016)

Magdalena Correa: La Rinconada (2012-2016)

The final piece in this latest set of 'Highlights' is La Rinconada (2012-2016), a series of photographs by Chilean artist Magdalena Correa taken in the town of the same name in the Peruvian Andes. Standing over 5,000 meters above sea level, La Rinconada is thought to be the highest permanently inhabited human settlement in the world. It owes its existence to a nearby gold mine (in a former glacier), in which most of the town's constantly fluctuating population are employed. The Banco de España has five pictures from the series, which, according to Carlos Martín, is expressed as a 'broken narrative sequence', documenting the 'particular forms of architecture, coexistence, conflict and changes to the landscape' generated by the labour system and the model of land use introduced here. Correa shows the contrast between the potential value of the gold and the precarious living and working conditions of the people who mine it. He also explores the continued importance of gold in financial capitalism – albeit it now has a more symbolic than material value – and confronts us with the phantom of the memory of colonialism and the unhealed wounds it inflicted on Latin America.