THE ARCHITECTURE OF EDUARDO DE ADARO AND THE BANCO DE ESPAÑA. A CHANGING WORLD

This exhibition is part of a larger project, launched in 2019, with a view to reinstating the figure of Eduardo de Adaro (b. Madrid, 6 February 1848 – d. Madrid, 27 February 1906). Adaro was one of the leading architects of the last three decades of the nineteenth century and was largely responsible for designing the Banco de España's original head offices.

His creativity and profound understanding of the technical and constructive innovations of his time, coupled with his familiarity with the workings of the banking system, allowed him to develop his own singular approach to bank design. In this, he drew on the knowledge and contributions of his predecessors —especially Severiano Sáinz de la Lastra— combining the palatial and the industrial, the technological and the artisan, the functional and the ceremonial, the traditional and the innovative. He applied this model not only to the bank's head office but also to the numerous branch offices he designed, as well as other private institutions, including the Banco Hispano Americano building at Plaza de Canalejas in Madrid. Given Adaro's important position and the fact that his fruitful career is now largely unknown, it was decided to launch a three-stage project to explore his legacy.

The first stage entailed a monographic study of his most iconic work, the nineteenth-century headquarters of the Banco de España, which also took in other lesser-known examples of his work in residential, prison, industrial and funerary architecture. The study, entitled Eduardo de Adaro. Arquitecto del Banco de España [Eduardo de Adaro. Architect of the Banco de España] is based on research by Professor of Art History Esperanza Guillén and may be downloaded free of charge from the Publications section of our website. As well as examining the architect's life and work, it also extends its focus to social and economic aspects of a country embroiled in a profound transformation. This volume describes the rapid construction of the Bank's head offices in Madrid between 1883 and 1891, an event which in many ways reflects the metamorphosis of fin-de-siècle Spain, from the consolidation of large-scale international trade in goods, backed by the development of overland and maritime communications, to the beginning of the country's technological dependence on powers such as Germany, France and Britain. Prof. Guillén's painstaking research in documentary, newspaper and photograph archives and other collections has also brought to light a wealth of information on some lesser-known aspects of the bank's construction. These include accidents on the construction sites, the appearance of the living quarters of bank employees and cashiers, the heating systems used in the office and some other novel and unusual innovations, including the sanitary facilities, which differed according to the rank of their intended users.

Once the research into Adaro's life had been completed, the second stage in the initiative involved commissioning an up-to-date photographic record of Adaro's work, to be added to the Banco de España's art collection. The series was entrusted to Manolo Laguillo, a leading figure in the world of documentary photography and one of the artists responsible for the recent renovation of architectural and urban photography in Spain. The commission extended not only to the bank building in Madrid, with its decorations and construction details, but also to other works by the same architect. The result is Adaro: un estudio de caso [Adaro: A Case Study], in which over three hundred pictures are compiled on six large contact sheets, to provide a novel look at Adaro's work. Our heritage collection also contains a selection of pictures from other photographic projects on Adaro's building, ranging from a series of shots taken by Jean Laurent et Cie. in the 1880s and 1890s, printed by Mallorcan photographer Juana Roig, to others made more than a century later by artists such as Javier Campano, Jorge Ribalta and Candida Höfer. It thus forges a link between some early works of Spanish documentary photography, dating more the closing decades of the nineteenth century, and others by contemporary artists who have contributed to the renovation of the genre.

The final stage in this project is the exhibition "The Architecture of Eduardo de Adaro and the Banco de España". Through a variety of documents, photographs, artworks and other items, it offers a selection of some of Adaro's principal contributions and provides a new understanding of this chapter in the bank's history and part of its artistic and documentary heritage. It also gives an insight into the changing world of fin-de-siècle Spain.

The exhibition is structured into five sections: ‘Origins of the New Banco de España Building’, ‘Security’, ‘The Money Palace’, ‘The Versatility of an Architect: Other Projects by Eduardo de Adaro’ and ‘Epilogue’. Most of the items on display are from the Banco de España's own collection and historical archive, although a significant number have been loaned by other private collectors and public institutions, including the National Science and Technology Museum, the Cerralbo Museum, the Madrid City Archives, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando, the History Museum of Madrid and the General Military Archives of Segovia.

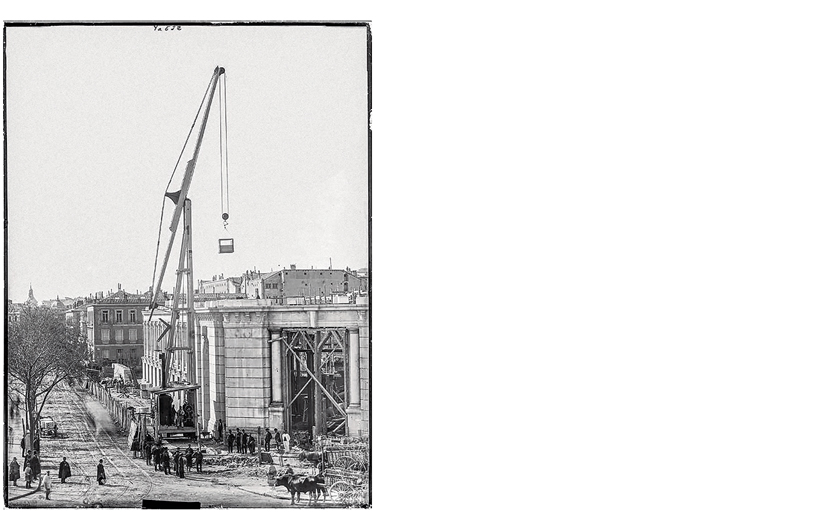

J. Laurent and Co. Banco de España en construcción [Banco de España under construction], ca.1886. Ruiz Vernacci Archives Collection, Spanish Cultural Heritage Institute, Ministry for Culture and Sports

ORIGINS OF THE NEW BANCO DE ESPAÑA BUILDING

Throughout the nineteenth century, Spain was engulfed in political turmoil, with the gradual loss of its colonial power. In 1874, the First Republic was superseded by the Bourbon Restoration. The country set about trying to recover some of its international prestige with the construction of a number of carefully designed and grandiloquent buildings. The new Banco de España headquarters —built to replace the former offices on Calle Atocha— is a prime example.

It came about as the direct result of the increased powers vested in the institution; a monopoly on the issuing of legal tender brought new needs for representation and other more practical requirements: for example, banknote production required more secure spaces to minimise the risk of counterfeiting. A call for tenders for the new building was published, but no suitable projects were submitted. The architects of the Banco de España —Severiano Sáinz de la Lastra and his young assistant, Eduardo de Adaro— were commissioned to draft a preliminary design for a building, which was to have an entrance on the corner of Plaza Cibeles and two similar façades on Calle Alcalá and Paseo del Prado. The site was soon expanded with the acquisition of further land and properties. To prepare for the task, Adaro visited some of the leading banks in Europe and on his return he drew up his first plans for the building. In 1884, the project won the first-class medal in the architecture section at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts. The first stone was laid in a solemn ceremony that same year, and the death of Sáinz de la Lastra catapulted Adaro into the position of chief architect.

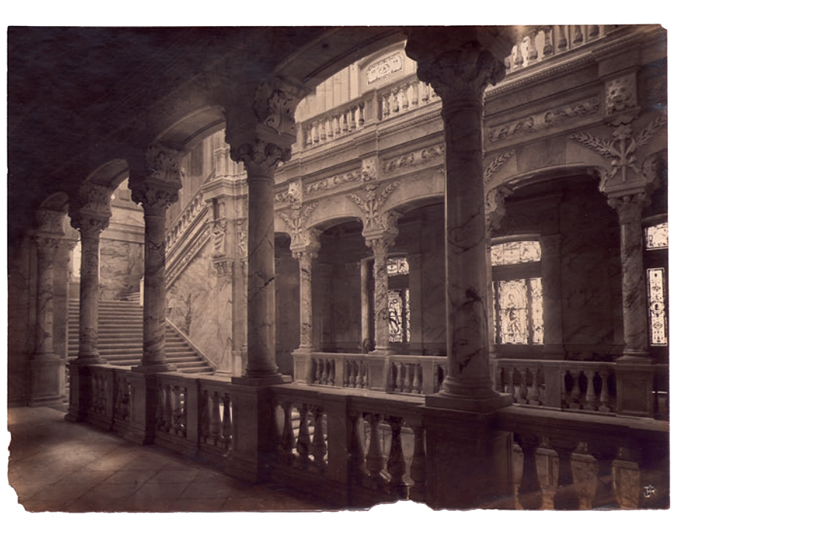

J. Laurent y Cía. Main staircase Chemically developed gelatin silver. Positive print by Juana Roig (1915-1921?). Historical Archive of the Banco de España, Photography Collection

This room shows some of the first steps in the construction of the building, with contemporary drawings and photographs. They include pictures taken by Laurent et Cie. and other unpublished photographs, together with documents on less well-known aspects, such as construction accidents on site. There are also a number of paintings from the collection's gallery of official portraits, which offers an almost uninterrupted record of the history of the institution since its creation as the Banco de San Carlos in 1782. They include a portrait by Valencian painter Joaquín Sorolla of the engineer, politician and writer José de Echegaray, during whose mandate as Treasury Minster the Banco de España was granted a monopoly on the issuing of banknotes, turning it into the country's leading financial institution.

SECURITY

Security was of prime importance in the design of the new building. By the time he started working on the design, Adaro already had extensive experience in this field. He applied his knowledge of prison architecture to the work at the Banco de España, which was the most advanced and complex of its time. It was designed in such a way that no one could enter the building unchecked and nothing valuable could be removed.

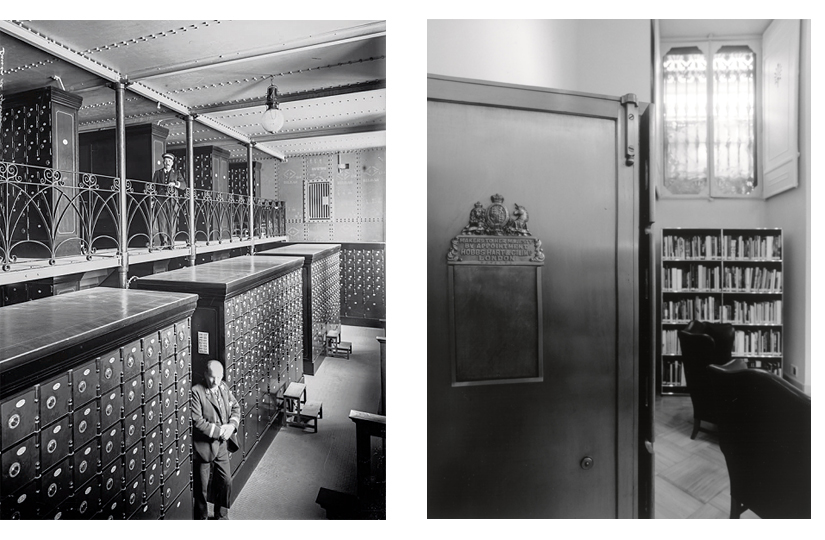

Banco de España safe-deposit boxes. Ruiz Vernacci Archives Collection, Spanish Cultural Heritage Institute, Ministry for Culture and Sports | Jorge Ribalta. From the series Restauración [Restoration]. Banco de España Collection

Iron bars were fitted to prevent access from the outside and special measures were taken in particularly sensitive areas such as the basement and semi-basement. These included extra-thick walls, vaults resting on granite pillars, walls reinforced with riveted iron plates and a parapet walk for the armed, uniformed guards. Particularly important, though, were the armoured doors leading to the safes that housed the cash, banknote production, jewellery and safe-deposit boxes. These were commissioned from Hobbs, Hart and Co. of London, with the requirement that they were to be of the same quality as those fitted 'in the vaults of the Bank of England'.

This room also hosts a documentary video, especially produced for the exhibition. which features some of Adaro's most important designs and buildings, not only for the banking sector, but also for industrial, prison, religious and residential constructions.

THE MONEY PALACE

Modern times, modern facilities

The design for the Banco de España building reflected Adaro's strong commitment to a modern architectural style and included all the latest technical advances.The architect travelled extensively throughout Europe and in 1889 he visited the celebrated Universal Exposition in Paris while he was preparing the facilities for the bank building, design for which was by then at an advanced stage.

Bell board (call indicator), ca. 1910. Wood, brass, paper, copper. National Science and Technology Museum | Wall-mounted telephone, ca. 1900. Wood, brass, chromed steel, coal, ebonite, copper, silk. National Science and Technology Museum | Desktop telephone, ca. 1910. Bakelite, cable, steel, cotton, silk, brass, wrought iron, paint, ebonite. National Science and Technology Museum

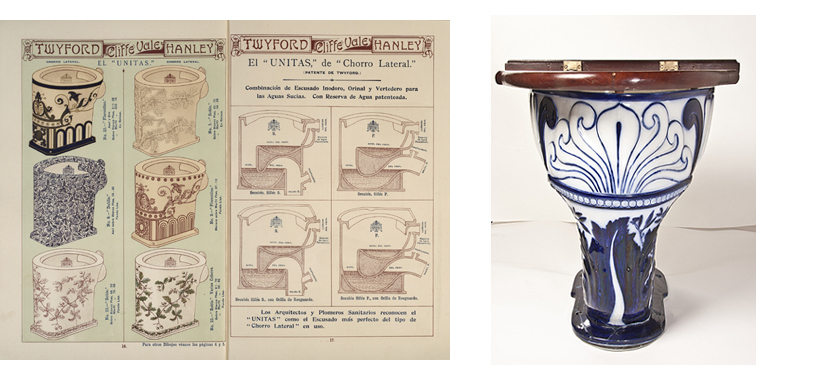

Twyford Hanley lavatory catalogue: Atkinson Bros Art Printers, 1893. Page 7 of the catalogue, Miguel Giménez Yanguas Collection: 'The Combination' lavatory. Doulton 1883-1900 Glazed and painted porcelain, Cerralbo Museum

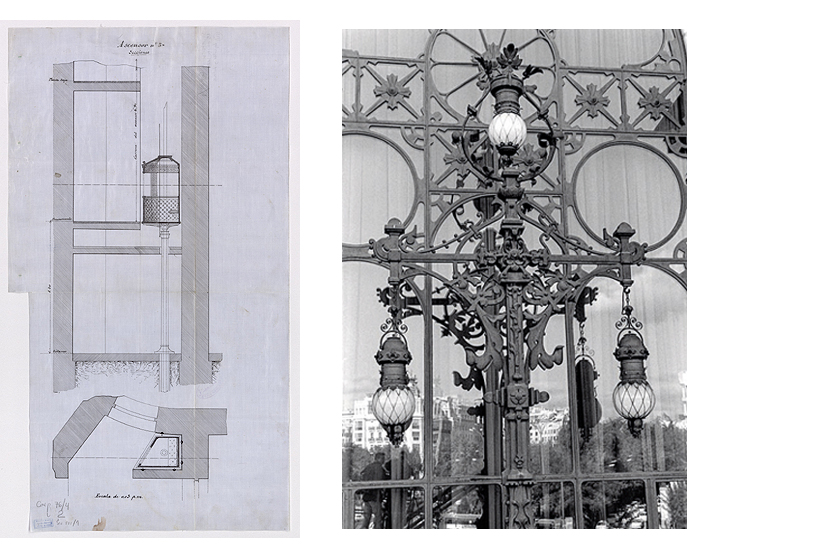

Adaro considered aspects such as light, communication, heating, hygiene and structural soundness to be of prime importance. He incorporated all the latest advances in heating systems, pneumatic tubes, mechanical locks, lifts, telephones, thermometers, barometers and, of course, electric lighting, which was installed from the outset to allow work on the new building to be completed in the shortest possible time, with labourers working night shifts. The design also included the latest protective features: as well as using iron, a modern industrial material that offered high levels of safety, Adaro also installed lightning rods and fire hydrants. He took a forthright, personal interest in improving hygiene conditions in all his buildings, a subject about which he wrote on several occasions.

All these features reflect a holistic fin-de-siècle approach to advanced architecture, which was viewed as being more than just a question of construction. This can also be seen in his choice of foreign suppliers for the facilities at the Banco de España, with names including AEG, Twyford, Saint-Gobain and Renton Gibbs. The bank spared no expense to equip the building with the finest materials and the latest technological advances.

The main staircase

The building's most significant feature —in terms of its grandiose design and lavish materials— is the staircase that ascends from the main vestibule on Paseo del Prado. Adaro, possibly working in collaboration with José María Aguilar, submitted numerous drawings and lists of materials, reflecting the importance he gave to this area.

Preparatory sketch for the stained-glass window depicting Fortuna [Fortune]. Mayer’sche Hofkunstanstalt GmbH - Mayer Archive, Munich Amor [Love], 1890. Stained glass. Banco de España Collection | Mayer. Felicitas, 1890. Stained glass. Banco de España Collection

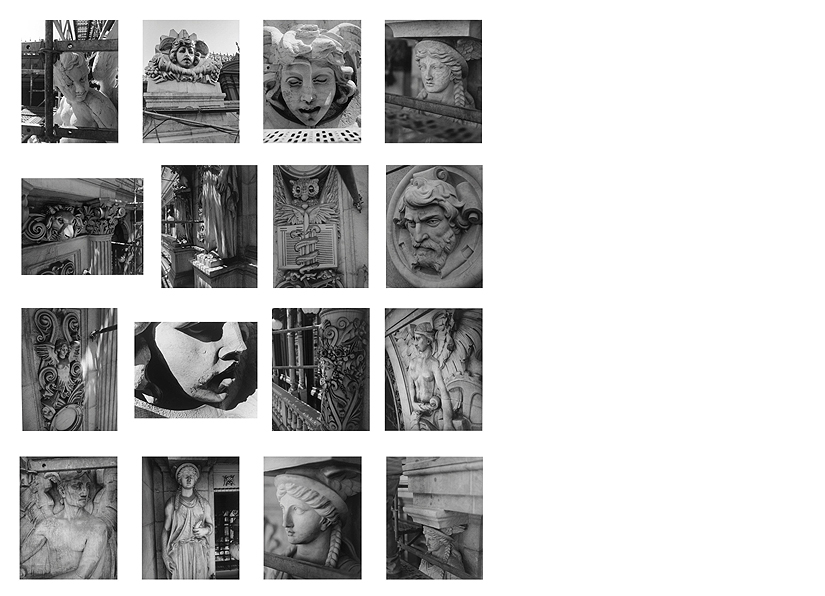

The lavish staircase was designed as a single piece, featuring sculpture-work in Carrara marble and plaster and stained-glass windows that add light and colour and draw attention to the space. The artwork in the reliefs contains references to the monarchy and classical gods alluding to prosperity. The figurative stained-glass windows, commissioned from Mayer's of Munich, form part of a more general movement of the time to reinstate the prestige of artisan workmanship. They show a series of allegories of virtues related to progress, commerce and industriousness, alluding to a new ethic of capitalism while at the same time exuding an air of imperial nostalgia.

Materials used in the architectural ornamentation

The materials selected in different areas of the building's exterior and interior reflect a moment of peculiar eclecticism in architectural history, in both style and materials. They show Adaro's willingness to select and combine the most appropriate features for each location, function or significance.

Attributed to Eduardo de Adaro (1848-1906) and José María Aguilar (1827-1899). Model of lifts 1 and 2 included with the bidding conditions for the tender for the installation of lifts in the Banco de España building. 15 March 1889. Black ink on canvas. Historical Archives of the Banco de España | Javier Campano. Iron bracket with arc lamps. From the series Edificio Banco de España [Banco de España Building] 2000-2001. Commissioned by the author. Banco de España Collection

Iron —the material that epitomised Spain's industrial progress— played a central role in Adaro's design. It was highly fire-resistant and allowed for wide unsupported spans. It also sped up construction, since the separate components were prefabricated and then assembled on site. In the Banco de España it was used in interiors and exteriors for construction and security purposes, but also as a decorative feature, referencing a wide variety of architectural styles.

The exterior stonework spoke to the building's public image. The stone references the strength of the institution. Further up on the façade it is more delicate, with medallions, panels, columns, caryatids and pilasters.

The assembly room, which hosted the annual general meeting of shareholders, was originally covered with profuse decorations in painted plaster. Today, however, only a few, hidden, fragments remain; in 1935, it was covered over with a second 'skin', making the room much starker, a far cry from its lavish appearance of yore.

Jorge Ribalta. Restauración [Restoration]. 2017. Gelatin silver bromide prints. Remarks: one of 6 compositions. Commissioned from the artist in 2016

THE VERSATILITY OF AN ARCHITECT: OTHER PROJECTS BY EDUARDO ADARO

Although Adaro is best known for his bank designs, he was a versatile architect who worked in a range of genres throughout his career, to which he always strove to apply innovative and often far-sighted solutions. His theoretical treatises and practical work deal with such diverse fields as industrial, religious, residential, prison and funerary architecture and even extend to the design of public monuments.

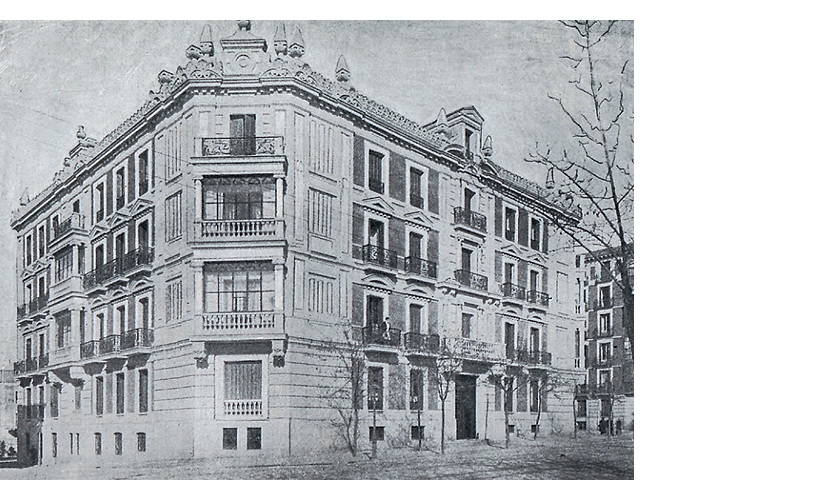

House designed by Eduardo de Adaro for Bruno Zaldo on Calle Alfonso XII, Madrid. Arquitectura y construcción, March 1906. Spanish National Library

There are numerous examples of his work dotted around Madrid, including some extant residential buildings on Calle Zurbano, Calle Juan de Mena and Calle Alfonso XII and a mansion-house on Calle Sagasta, which reflect his long-term collaboration with different developers from the elite circles of the financial and industrial world. Others include the La Industrial Madrileña biscuit factory —since demolished— and the Pantheon of the Marquis of Casa-Jiménez in the San Isidro Cemetery.

Eduardo de Adaro (1848-1906). Main façade of the residential building designed for Bruno Zaldo on Calle Alfonso XII, Madrid. 15 September 1901. Ink drawing on treated canvas. Madrid City Archives. Madrid City Council

Outside the capital, one of his most significant designs was for a prison (never built) on the island of Cabrera, in which he brought to bear his enlightened, humanistic ideology in resolving the problems inherent to this field. The same awareness can be seen in his contributions to the reconstruction of areas of Granada and Malaga devastated by the 1884 earthquakes, where his disinterested work included his only designs for religious buildings.

EPILOGUE

Banco de España Branches

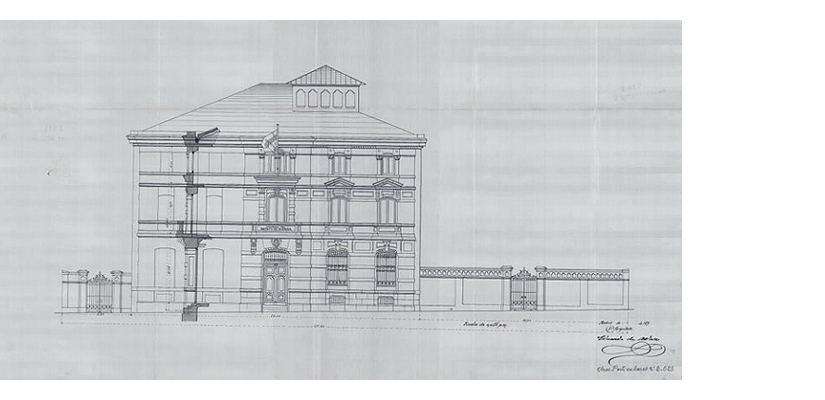

The Banco de España built branch offices across the country, ensuring a local presence for the institution and providing a nationwide service. As part of this programme, Adaro designed the offices in Burgos, Huesca, Logroño and Pontevedra (although the latter was subsequently the subject of major alterations). He also remodelled many existing branches. The branches were originally sited in rented premises, but many were either too small, in poor condition, or lacked security features and the bank decided to purchase land to build new buildings.

Eduardo de Adaro. Elevation drawing of the Banco de España branch in Burgos submitted with the application for the new building, 1898. Municipal archives of Burgos

The appointment of Adaro to design these new offices reflected his ability to forge the image the bank wanted to project and to adapt to specific contexts, in dialogue with the local cultural background and environment. This is demonstrated by his use of brick for the Huesca branch, a crenelated fortress-like construction with a hint of the Mudejar, and the brick-and-stone design on the façades of the Logroño and Burgos branches. The latter also had gardens which Adaro wanted to make visible from the outside, by fitting iron railings, to create a dialogue with the exterior and the wider city.

Head offices of the Banco Hispano Americano in Madrid

Adaro's final project was also for a bank and, together with the Banco de España, was to become his most important commission. This was the design for the head offices of the Banco Hispano Americano, founded by a group of industrialists with overseas economic interests and shareholders who wanted to strengthen commercial ties with the Americas.

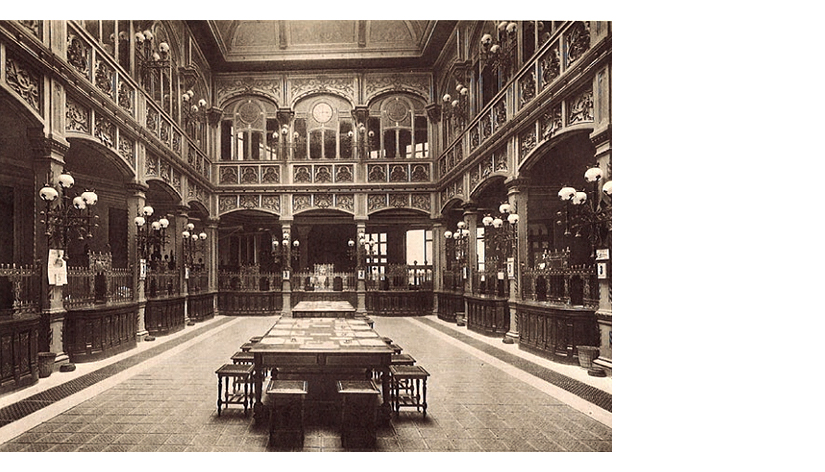

Banco Hispano Americano. Head offices, Madrid. Central courtyard. Banco Hispano Americano (1926): XXV aniversario. Historical Archives of the Banco Santander

The building is located at the junction of Carrera de San Jerónimo and Calle de Sevilla, on the square now called Plaza de Canalejas. It underwent internal alterations in the 1940s and has now been incorporated into a hotel and shopping complex, with major changes to the original appearance of the building and a clear change in height. For the irregularly shaped site, Adaro designed a distinctive curved façade which adds its own personality to the square. The new offices earned him enthusiastic reviews and unanimous recognition in official circles and in February 1906, just a few years before his death, he was awarded the Grand Cross of Alfonso XII for the design.

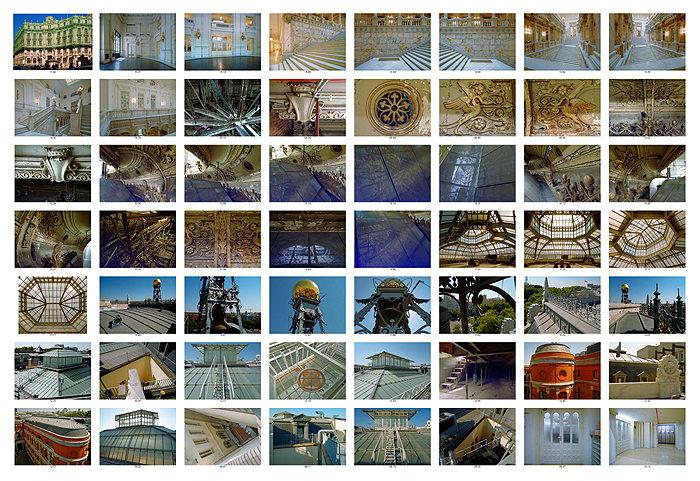

The Banco Hispano Americano offices are both a testament to and a compendium of Adaro's architecture, and this room offers a summary in photos of all his work, in a series by Manolo Laguillo entitled Adaro: A Case Study. It consists of a compilation of monumental contact sheets, which together provide a final visual reflection on the complete works of an architect who helped define an era.

Manolo Laguillo. Adaro: A Case Study, 2021. Giclée (pigmented inks on archival-quality pH-neutral paper). Commissioned to the author in 2021. Remarks: one of 6 compositions. Banco de España Collection

EDUARDO DE ADARO (1848-1906). DOCUMENTARY

To coincide with the exhibition The Architecture of Eduardo de Adaro and the Banco de España. A Changing World, Tatiana Poggi and Joaquín García Vicente of ESPECIE Arquitectura have made a documentary on the life of the man largely responsible for designing the Banco de España's original head offices, and one of the most important architects of the latter decades of the nineteenth century.