Shedding new light on Sorolla

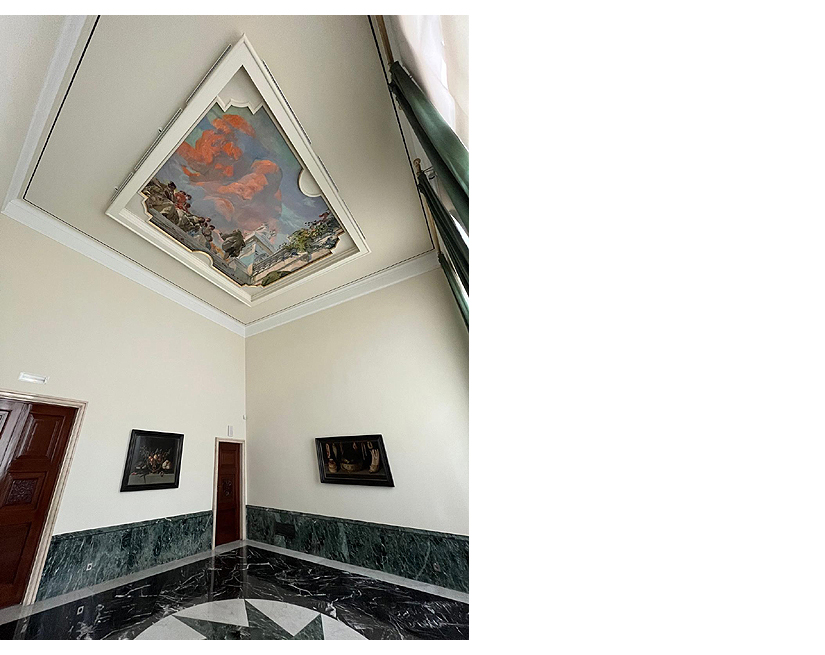

Voltaire Telling a Story (1905) is considered to be atypical in the oeuvre of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (b. Valencia, 1863 – d. Cercedilla, Madrid, 1923). It was the centrepiece of his decoration for a ceiling at the home of Calixto Sánchez — a forestry engineer, who had an enduring friendship with Sorolla and acquired more than ten of his paintings. The piece belongs to a genre known as casacón painting (associated with the French tableautin movement), which was much in vogue in the nineteenth-century among Spain's upper middle classes. It demonstrates the Valencian painter's technical mastery, not only in his skilful brushstrokes but also in his use of perspective. Voltaire Telling a Story is intended to be observed from ground level, and the artist masterfully achieves a sense of depth through careful use of architectural features.

The picture is believed to depict the French writer recounting his short story Platon's Dream, a hypothesis that is partly based on the fact that above the heads of Voltaire (shown with his back to the viewer) and his listeners, we can see a spectral form made up of clouds or mountains, representing a figure lost in thought, who could credibly be the Greek philosopher. Moreover, Mónica Rodríguez Subirana has noted that the story was in an anthology by Voltaire that Sorolla had in his library (the book is still preserved in the Sorolla Museum![]() ).

).

To one side of the canvas, outside the central group, is a girl leaning on a balustrade, looking down and out of the immediate field of the painting. Sorolla uses this simple but effective detail to reinforce the veracity of the perspective, while at the same time incorporating a component from everyday life, a key element in his aesthetic approach. Given her age, it is reasonable to assume that the girl may be the artist’s daughter, Elena.

The Banco de España acquired the painting in 1970. It has now been restored as part of a collaboration agreement signed in 2013 between the bank and the Museo del Prado![]() , under which sixteen artworks have been restored to date. These include the recently restored portrait of José de Toro-Zambrano y Ureta, the first of six pictures painted by Francisco de Goya for the Banco de San Carlos between 1784 and 1788.

, under which sixteen artworks have been restored to date. These include the recently restored portrait of José de Toro-Zambrano y Ureta, the first of six pictures painted by Francisco de Goya for the Banco de San Carlos between 1784 and 1788.

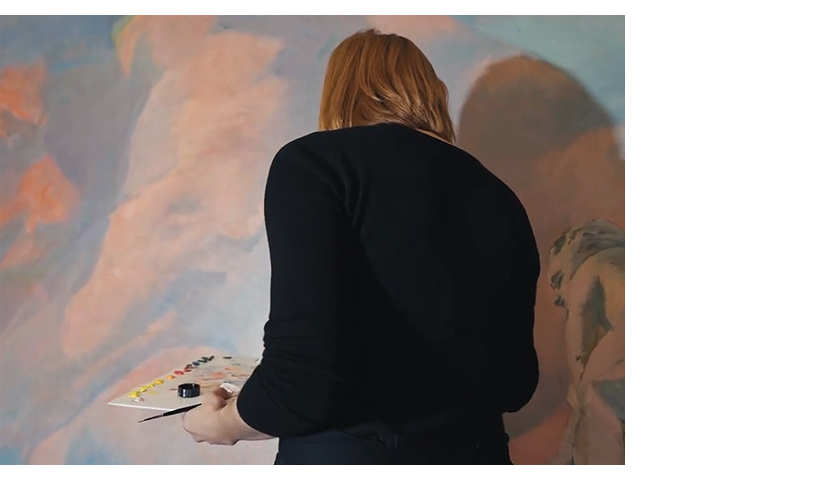

The decision to restore the Sorolla – almost four metres in length – was taken when renovation was being scheduled on the area where it is located, which meant the canvas had to be taken down to ensure its safety. On close inspection, staff concluded that it required complex restoration work, including in-depth cleaning of the paint, which was seriously affected by dust and pollution. Some repainted areas also needed to be retouched to make the varnish more uniform and repair occasional losses in the pictorial layer. The ultimate aim was to restore the original texture and luminosity of the original painting.

The restoration was carried out by the team from the Prado, headed by Lucía Martínez Valverde and Lorena Fernández. Praising their excellent work, Yolanda Romero, chief conservator at the Banco de España, said that the 'luminous quality' of the work can now be much better appreciated; ‘the work will ensure the conservation of the painting for posterity, thus fulfilling one of the bank's main duties as regards its heritage collection'. The bank is also very grateful to the Sorolla family for their invaluable help in locating a preparatory cartoon made by the artist for the painting. The discovery gave restoration staff a first-hand idea of the artist's intentions and enabled them to reconstruct part of the original painting that had been covered over by one of the semicircles in the perimeter moulding on the ceiling.

The restoration was carried out by the team from the Prado, headed by Lucía Martínez Valverde and Lorena Fernández. Praising their excellent work, Yolanda Romero, chief conservator at the Banco de España, said that the 'luminous quality' of the work can now be much better appreciated; ‘the work will ensure the conservation of the painting for posterity, thus fulfilling one of the bank's main duties as regards its heritage collection'. The bank is also very grateful to the Sorolla family for their invaluable help in locating a preparatory cartoon made by the artist for the painting. The discovery gave restoration staff a first-hand idea of the artist's intentions and enabled them to reconstruct part of the original painting that had been covered over by one of the semicircles in the perimeter moulding on the ceiling.

In addition to Voltaire Telling a Story, the bank has three other works by Sorolla: Portrait of José Echegaray (1905), commissioned by the Casino de Madrid when the playwright was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature; In the Tavern. Zarauz (1910), a fine example of his way of painting anonymous characters in intimate scenes that function almost as portraits, not only in their physical appearance but also in their depiction of customs; and Old Door of Seville Cathedral (1910), an oil painting of the Nativity Door at Seville Cathedral, which was included in some of Sorolla's great solo exhibitions in the US.