Banco de España loans nine artworks from its collection for exhibitions in Madrid, Murcia and Malaga this autumn

The Banco de España regularly loans out items from its collection for temporary exhibitions at Spanish and foreign museums. It is one of a number of initiatives to highlight its strong commitment to providing broader public access to its historical and artistic heritage. This autumn, nine works from the collection will be on show in exhibitions in Madrid, Murcia and Malaga. The five shows are Soledad Sevilla. Rhythms, Grids, Variables![]() and In the Troubled Air

and In the Troubled Air![]() at the Museo Reina Sofía; Alfonso Albacete. La pintura inevitable [Inevitable Painting]

at the Museo Reina Sofía; Alfonso Albacete. La pintura inevitable [Inevitable Painting]![]() , at the Fundación Cajamurcia; Naked. Normative and Rebellious Nudes in Spanish Art (1870-1970)

, at the Fundación Cajamurcia; Naked. Normative and Rebellious Nudes in Spanish Art (1870-1970)![]() at the Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga and Sorolla, One Hundred Years of Modernity

at the Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga and Sorolla, One Hundred Years of Modernity![]() , at the Royal Collections Gallery. Also this year, two works by Eduardo Chillida and Manuel Millares featured in A Conversation: Chillida and the Arts. 1950-1970

, at the Royal Collections Gallery. Also this year, two works by Eduardo Chillida and Manuel Millares featured in A Conversation: Chillida and the Arts. 1950-1970![]() at the San Telmo Museum in Donostia / San Sebastian, which ended on 29 September.

at the San Telmo Museum in Donostia / San Sebastian, which ended on 29 September.

Rhythms, Grids, Variables![]() will run at the Museo Reina Sofia until 10 March 2025. Curated by Isabel Tejeda, the exhibition takes a chronological look at the career of Soledad Sevilla (b. Valencia, 1944), with over a hundred of her works spanning six decades. The Banco de España collection has four works by Sevilla, who won the Velázquez Prize for Plastic Arts in 2020. They all date from the early 1980s, when the artist was living and working in Boston, on a research fellowship to study at Harvard University from the Spanish-American Joint Committee on Educational Affairs. It marked an important turning point in her career, leading her to focus increasingly on poetic and emotional aspects.

will run at the Museo Reina Sofia until 10 March 2025. Curated by Isabel Tejeda, the exhibition takes a chronological look at the career of Soledad Sevilla (b. Valencia, 1944), with over a hundred of her works spanning six decades. The Banco de España collection has four works by Sevilla, who won the Velázquez Prize for Plastic Arts in 2020. They all date from the early 1980s, when the artist was living and working in Boston, on a research fellowship to study at Harvard University from the Spanish-American Joint Committee on Educational Affairs. It marked an important turning point in her career, leading her to focus increasingly on poetic and emotional aspects.

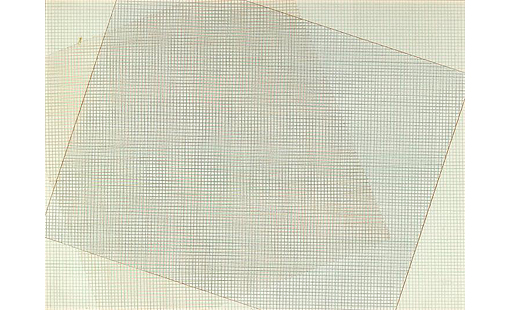

Soledad Sevilla: Las Meninas IV (1982)

Soledad Sevilla: Las Meninas IV (1982)

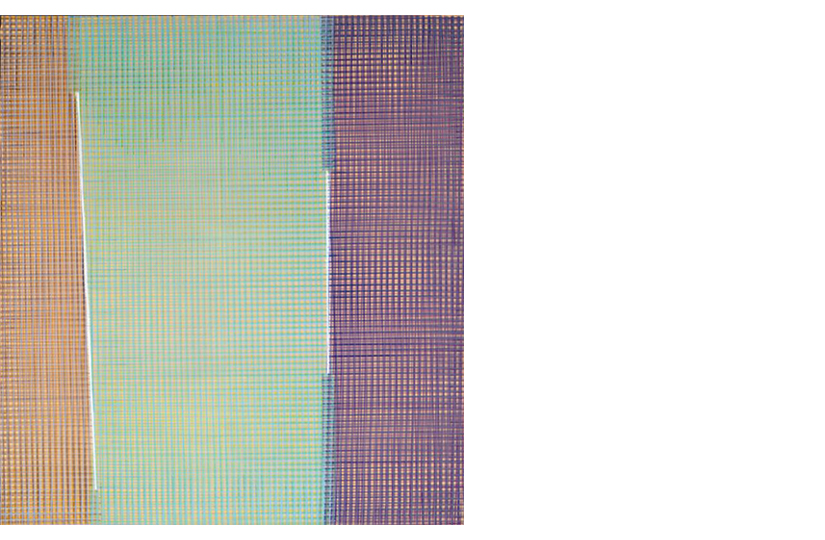

Las Meninas IV (1982) is one of a series of paintings centring on Velázquez's celebrated painting of the same name. What interests Sevilla about the original painting, notes Yolanda Romero, are not the characters or the overlapping stories within the picture, but rather the way in which Velázquez configures the space, the venue of the painting, using the immaterial element of light. Sevilla's use of superimposed quadrangular lattices, modulated with colour, represent a major shift in her previous research on geometric grids. This change can already be seen in the series immediately preceding this one, Belmont (named after the suburb of Boston in which the artist lived during her time in the US). The three drawings from this series in the Banco de España collection — Belmont VI, Belmont VII and Belmont VIII — have also been loaned for the retrospective at the Museo Reina Sofía.

Soledad Sevilla: Belmont VII (1982) | Belmont VIII (1982)

Soledad Sevilla: Belmont VII (1982) | Belmont VIII (1982)

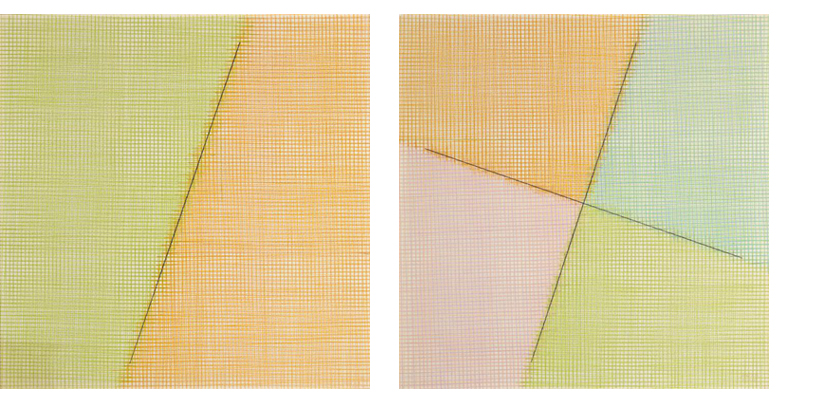

Dating from around the same period as the Belmont and Meninas series are two paintings in the collection by Alfonso Albacete (b. Antequera, Málaga, 1950), María (1981) and First Ulysses (Still Life with Lemons) (1981), which are now on display in La pintura inevitable![]() [Inevitable Painting], an exhibition of the artist's work which opened in early October at Fundación Cajamurcia's Las Claras Cultural Centre in Murcia. The two are early examples of 'painting for painting’s sake', a notion championed by Albacete in the early 1980s. This retrospective is also being curated by Isabel Tejeda, who writes that at this time, Albacete turned his back 'on metalinguistic discourses to immerse [himself], almost hedonistically, in the pleasure of painting'. In his reaffirmation of the pictorial genre, the artist engaged in a reinterpretation of classic genres, such as portraiture — as is the case with María, where the space is expressed using brush strokes that construct the place of a body located in the centre of the canvas — and still life, with First Ulysses (Still Life with Lemons) recalling his childhood and youth in La Alberca, Murcia, where he first began painting under the tutelage of his teacher, Juan Bonafé.

[Inevitable Painting], an exhibition of the artist's work which opened in early October at Fundación Cajamurcia's Las Claras Cultural Centre in Murcia. The two are early examples of 'painting for painting’s sake', a notion championed by Albacete in the early 1980s. This retrospective is also being curated by Isabel Tejeda, who writes that at this time, Albacete turned his back 'on metalinguistic discourses to immerse [himself], almost hedonistically, in the pleasure of painting'. In his reaffirmation of the pictorial genre, the artist engaged in a reinterpretation of classic genres, such as portraiture — as is the case with María, where the space is expressed using brush strokes that construct the place of a body located in the centre of the canvas — and still life, with First Ulysses (Still Life with Lemons) recalling his childhood and youth in La Alberca, Murcia, where he first began painting under the tutelage of his teacher, Juan Bonafé.

Alfonso Albacete: First Ulysses (Still Life with Lemons) (1981)

Alfonso Albacete: First Ulysses (Still Life with Lemons) (1981)

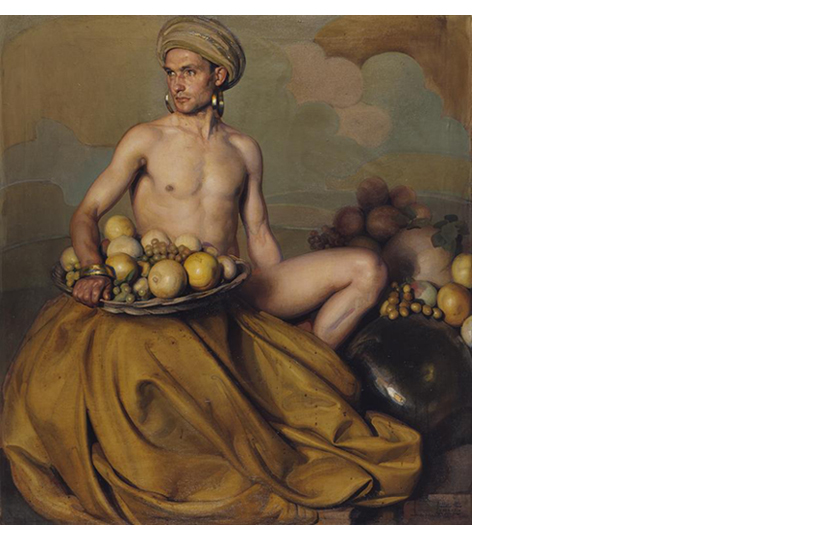

Dating from almost half a century before the works by Sevilla and Albacete, God of Fruit (1936) is one of the last nudes painted by Gabriel Morcillo (Granada 1887 - 1973), with remarkable material qualities. Working in a late symbolist style, it was a genre he had cultivated between 1914 and 1936, but he was forced to stop painting nude subjects after the outbreak of the Civil War. As Javier Moya explains, his nudes 'are rarely, if ever, depicted in full. Physically the subjects are always of a sort of fibrous slenderness, [...] vaguely inspired by Arab-Andalusian literature and the tales and legends of Chateaubriand and Washington Irving'. This imagery — which would today be described as Orientalist — is reinforced by the contrived settings in which he places his characters. According to Moya, it is a style that denotes 'a clear continuation of academic modes that eschews any alignment with the art movements of his time'. This academicist conservatism, however contrasts with the suggestions of homo-eroticism in his work, making him highly unusual among the artists of his time. The painting by Morcillo has been loaned to the Museo Carmen Thyssen Málaga for Naked. Normative and Rebellious Nudes in Spanish Art (1870-1970), an exhibition of nearly ninety works by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Julio González, Maruja Mallo, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Antonio Saura and Menchu Gal.

Gabriel Morcillo: God of Fruit (1936)

Gabriel Morcillo: God of Fruit (1936)

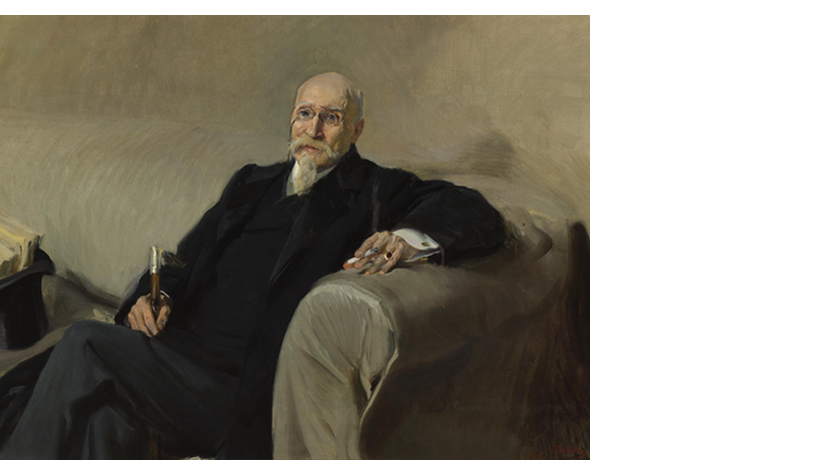

Also currently out on loan is the portrait of José de Echegaray painted by Joaquín de Sorolla in 1905, which is on show in Sorolla, One Hundred Years of Modernity![]() at the Royal Collections Gallery, which concludes the events to mark centenary of the artist's death. Commissioned by the Casino de Madrid to celebrate the award of the 1904 Nobel Prize for Literature to the playwright, it reflects Sorolla's mastery as a portrait artist. Despite being a late convert to the genre, he came to excel in the last two decades of his career. Echegaray is depicted with a smile; he is elegantly dressed and holds a cigarette in one hand and a cane in the other. To his right stands a hat from which a number of books protrude. This detail — as Mónica Rodríguez Subirana has noted — is a reference to Echegaray's facet as a writer, although he was also renowned as an engineer and a politician. Indeed, he played a key role in the Banco de España's development, since it was during his tenure as Minister of Finance that the institution was granted a monopoly on the issue of banknotes, thus turning it into the national bank.

at the Royal Collections Gallery, which concludes the events to mark centenary of the artist's death. Commissioned by the Casino de Madrid to celebrate the award of the 1904 Nobel Prize for Literature to the playwright, it reflects Sorolla's mastery as a portrait artist. Despite being a late convert to the genre, he came to excel in the last two decades of his career. Echegaray is depicted with a smile; he is elegantly dressed and holds a cigarette in one hand and a cane in the other. To his right stands a hat from which a number of books protrude. This detail — as Mónica Rodríguez Subirana has noted — is a reference to Echegaray's facet as a writer, although he was also renowned as an engineer and a politician. Indeed, he played a key role in the Banco de España's development, since it was during his tenure as Minister of Finance that the institution was granted a monopoly on the issue of banknotes, thus turning it into the national bank.

Joaquín de Sorolla: Portrait of José Echegaray (1905).

Joaquín de Sorolla: Portrait of José Echegaray (1905).

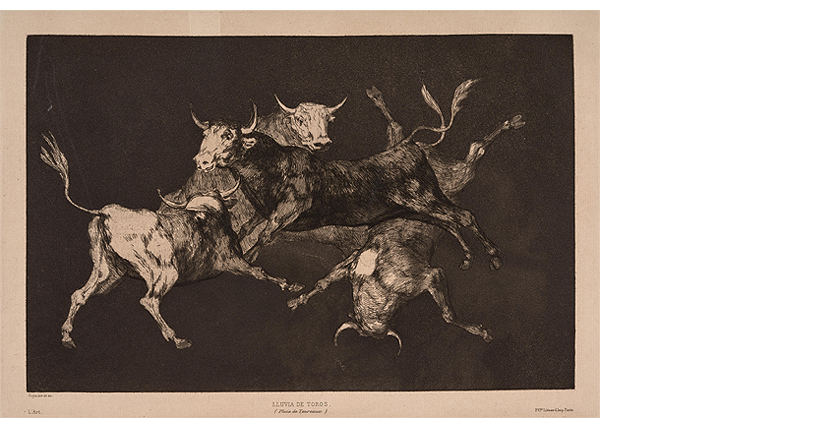

Dating from almost a century before Echegaray's portrait are the four prints in the series of Follies [Disparates] by Francisco de Goya in the collection. One of them, entitled Rain of Bulls [Folly of Little Bulls], is currently hanging in In the Troubled Air![]() , an exhibition being jointly organised by the Museo Reina Sofía

, an exhibition being jointly organised by the Museo Reina Sofía![]() and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

and the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona![]() (CCCB). The show, which includes a large selection of artworks and documentary sources 'sets forth a political anthropology of emotion in a poetic tone'. The four prints became separated from the rest of the series and were only published until 1877, when they were featured in the Paris magazine L'Art. They are valuable not only as artworks by Goya, but as a product and record of the prevailing aesthetic of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. According to José Manuel Matilla Rodríguez, like the Black Paintings, the series perfectly demonstrates Goya's position as a forerunner of modernism and the way in which he broke with the prevailing logic of imitation, placing the artist's imagination and subjectivity at the heart of his work.

(CCCB). The show, which includes a large selection of artworks and documentary sources 'sets forth a political anthropology of emotion in a poetic tone'. The four prints became separated from the rest of the series and were only published until 1877, when they were featured in the Paris magazine L'Art. They are valuable not only as artworks by Goya, but as a product and record of the prevailing aesthetic of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. According to José Manuel Matilla Rodríguez, like the Black Paintings, the series perfectly demonstrates Goya's position as a forerunner of modernism and the way in which he broke with the prevailing logic of imitation, placing the artist's imagination and subjectivity at the heart of his work.

Francisco de Goya: Rain of Bulls [Folly of Little Bulls] (1815-1824)

Francisco de Goya: Rain of Bulls [Folly of Little Bulls] (1815-1824)

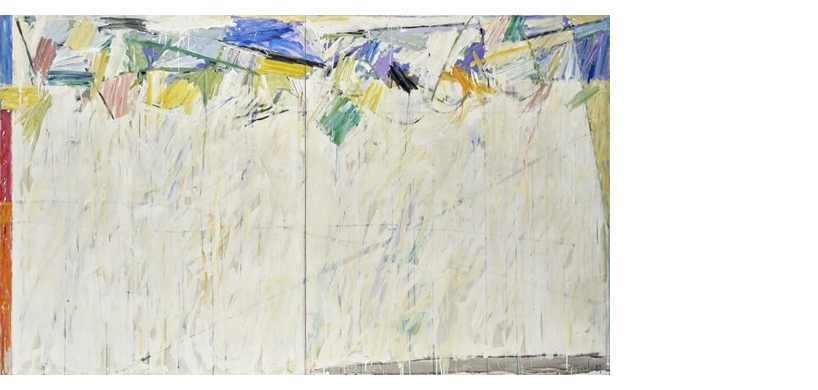

Another two works from the Banco de España collection were out on loan for the exhibition A Conversation: Chillida and the Arts. 1950-1970![]() at the San Telmo Museum, which concluded at the end of September. These were Murmur of Limits I (1958), a sculpture by Eduardo Chillida (Donostia / San Sebastián, 1924 - 2002) in which the iron is constructed as a line that draws a pattern in space, vibrating in its encounter with the air until it acquires an apparent and paradoxical weightlessness; and Humboldt on the Orinoco (1969), by Manolo Millares (b. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1926 – d. Madrid, 1972), made during the final years of his career. It shows how Millares' later work came close to colour field painting, as he displayed an increasing interest in exploring the abyss and the unknown.

at the San Telmo Museum, which concluded at the end of September. These were Murmur of Limits I (1958), a sculpture by Eduardo Chillida (Donostia / San Sebastián, 1924 - 2002) in which the iron is constructed as a line that draws a pattern in space, vibrating in its encounter with the air until it acquires an apparent and paradoxical weightlessness; and Humboldt on the Orinoco (1969), by Manolo Millares (b. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1926 – d. Madrid, 1972), made during the final years of his career. It shows how Millares' later work came close to colour field painting, as he displayed an increasing interest in exploring the abyss and the unknown.

Eduardo Chillida: Murmur of Limits (1958) | Manolo Millares: Humboldt on the Orinoco (1969)

Eduardo Chillida: Murmur of Limits (1958) | Manolo Millares: Humboldt on the Orinoco (1969)