![Daniel García Andújar: 'falso_de_época' (2020) [detalle]](/f/webca/ADS/Noticias/NotDGAimgport01.jpg)

'Period Fake’, an unorthodox journey through the world of forgery

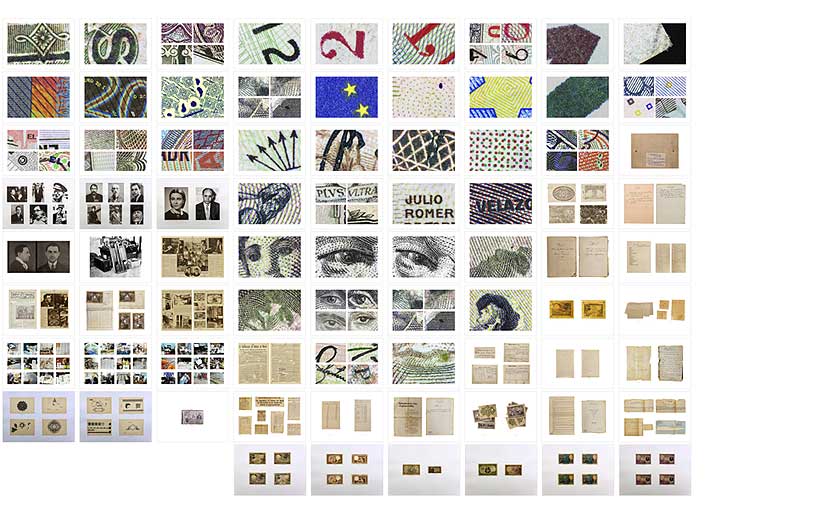

Daniel García Andujar (b. Alicante 1966) began his career in the early 1990s. He is both an artist and a theorist. His hybrid, markedly process-oriented projects place great emphasis on archive work. Period Fake (2020) was produced on commission from the Banco de España. It is an investigation into the history of bank-note forgery that highlights the meeting point between two ongoing debates in the world of contemporary art: original vs copy and authenticity as a symbolic construct. It also looks at the implications of the radical changes brought about by the onset of information and communication technologies, as most financial transactions come to be carried out digitally. This tendency has been further accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The investigation has given rise to what García Andújar![]() describes as an "iconoclast's atlas". He describes this compilation of widely varying materials as a blend of "stories of crime" drawn from expert reports published by the Investigation Brigade of the Banco de España and other sources, covering political activism and the clandestine struggle against the Franco regime. They include the story of Mariano Conde

describes as an "iconoclast's atlas". He describes this compilation of widely varying materials as a blend of "stories of crime" drawn from expert reports published by the Investigation Brigade of the Banco de España and other sources, covering political activism and the clandestine struggle against the Franco regime. They include the story of Mariano Conde![]() , "the most famous forger to emerge from the Spanish picaresque tradition". Then there is Laureano Cerrada

, "the most famous forger to emerge from the Spanish picaresque tradition". Then there is Laureano Cerrada![]() , "perhaps the greatest, best known forger of the militant anarchist movement", who set up a whole team of forgers including the cartoonist Guillembert and the libertarian artist and engraver Madeleine Lamberet

, "perhaps the greatest, best known forger of the militant anarchist movement", who set up a whole team of forgers including the cartoonist Guillembert and the libertarian artist and engraver Madeleine Lamberet![]() , with the intention of ruining the Spanish economy in the years immediately following the Civil War. More recently, in the age of the euro, there is Murcia-born Juan Pedro González Sánchez

, with the intention of ruining the Spanish economy in the years immediately following the Civil War. More recently, in the age of the euro, there is Murcia-born Juan Pedro González Sánchez![]() , who "made the collective fantasy of making money without leaving home come true".

, who "made the collective fantasy of making money without leaving home come true".

Daniel García Andújar: Period Fake (2020)

Daniel García Andújar: Period Fake (2020)

All these stories belong to a world now confined to the archives which will soon be unrecognisable. Actual physical money is being used less and less. As currency becomes a digital cryptoasset that works via a decentralised database, so traditional forgers are gradually being displaced by hackers capable of decoding encryption algorithms. That is why Daniel García Andújar has chosen to present his work in the form of an atlas, taking the archives and documents held by the Banco de España as his source for investigating the formal, technical and historiographic issues that are key to understanding the development, transformations and shifts in the "art" of forging bank-notes. Notes became the main form of payment in European societies in the 18th and 19th centuries, i.e. at the time when the great national banks were beginning to appear.

"Paper money is literally just a piece of paper that forms part of the structure of the movement of capital" he explains. It carries designs, marks and signatures intended to help guarantee its authenticity. What used to be done by craftsmen is now done by increasingly complex computer programs, but the goal is the same: to prevent tampering or at least render it easily detectable. The fight against forgery is a constant feature of the history of bank-notes. Indeed, the oldest known note, a Yuan dated 1376, bears a warning of the punishment meted out to forgers. Daniel García Andújar links this with the debate on the notion of "original works" in art. That debate has come to the fore recently as digital technology has begun increasingly to blur the limits of authorship, so that the difference between originals and copies (between reality and fiction or between the authentic and the artificial) is harder and harder to pin down.

Daniel García Andújar: Capital, Merchandise. Guilloché (2015)

Daniel García Andújar: Capital, Merchandise. Guilloché (2015)

Period Fake, with its wide variety of materials including documents from the archives of the Banco de España, press cuttings, photos, images produced using sophisticated forensic techniques and real and forged bank-notes, is not the first project in which he has been involved with bank notes as a medium for art. Guilloché (2015), which also forms part of our Collection, involved designs for eighteen notes using an IT application that digitally reproduced guilloche, a technique which is widely used in numismatics. The bank-notes produced featured an unusual repertoire of images alluding to today's world and its conflicts, reflecting the idea that the themes and iconographic elements used traditionally on notes reveal the dominant world-view and ideology of their times. Guilloché is the third part of a cycle of works under the generic title Capital. Goods![]() , which García Andújar produced in the mid 2010s. For the project, he delved into the so-called Deep Web

, which García Andújar produced in the mid 2010s. For the project, he delved into the so-called Deep Web![]() to investigate the clandestine financial transactions that abound there: transactions associated with dissident or unlawful activities usually paid for in bitcoins.

to investigate the clandestine financial transactions that abound there: transactions associated with dissident or unlawful activities usually paid for in bitcoins.