The latest update to our 'Highlights' section features three works currently on show in the 'Tyranny of Chronos' exhibition

Our Collection section of our website regularly features some of the 4,500 artworks from diverse periods in very different styles and formats that are held in the Banco de España collection. We have now updated the section to include three pieces from the current exhibition at the bank, The Tyranny of Chronos. These are Jan Leyniers's tapestry Triumph of Love and Eternity over Time, the oldest piece in the exhibition; Clocks, by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, a leading light in Spanish conceptual art; and Viral Diary, a collage by Inmaculada Salinas, a critical connection in which she draws parallels between the way in which she has been obliged to align her art with the rules of capitalist productivity, on the one hand and her experience and memories of the Covid-19 lockdown on the other.

Jan Leyniers II: Triumph of Love and Eternity over Time (1684)

This piece occupies pride of place at the centre of the exhibition, immediately opposite Annie Leibovitz's portraits of King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia. Triumph of Love and Eternity over Time is an imposing tapestry made in 1684 by Jan Leyniers II, a member of one of the leading Brussels tapestry-making families of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Leyniers based the piece on a composition by painter David Teniers III, who specialised in designing cartoons for tapestries with an especially sensitive eye for the symbolism of his time.

Critic Antonio Sama writes that this piece exemplifies a period in Western tapestry in which heraldry and moral allegory were closely intertwined, resulting in 'woven hieroglyphs'. At the centre of the piece is the coat of arms of the López de Ayala family, the counts of Fuensalida. Beneath it, a winged old man is being bound in chains by an amorino, while an hourglass and a scythe lie at his side. These two attributes, together with the wings, identify the individual as Chronos or, to use historian Erwin Panofsky's term, 'Father Time', a classical mythological motif retrieved in the Modern Era, inevitably through the prism of medieval reinterpretation.

What makes this composition unique is that it eschews the prevalent contemporary representation of Chronos as a triumphant figure (inseparable, according to Sama, from 'the Baroque obsession with the passage of time and the genre of the vanitas'). Instead, we see the titan being subdued by Cupid's arts, causing him to lose the attributes whereby he controls time. To understand the full complexity of Teniers' allegorical interpretation, notes Sama, we also need to consider the winged maiden holding the coat of arms. In one of her hands, she is holding an ouroboros — a circle-shaped serpent eating its own tail symbolising eternal renewal. This identifies her as the personification of Eternity which, with Love, has halted the ravages of Time.

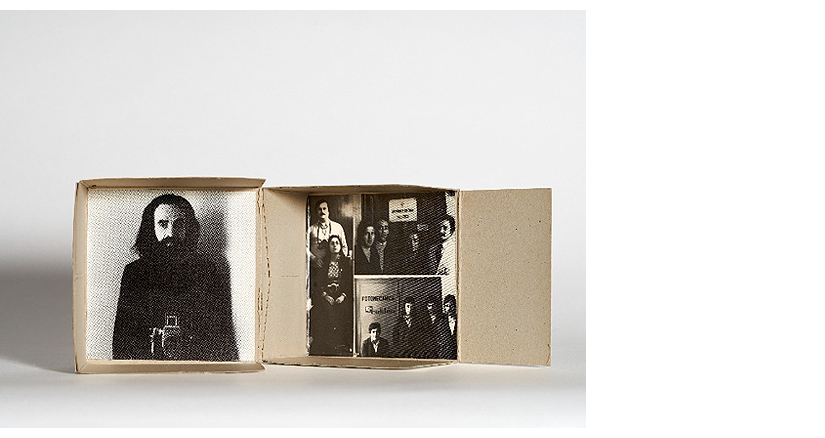

Isidoro Valcárcel Medina: Clocks (1973)

The second featured work is Clocks (1973), one of the first projects in the public art period begun by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina after his participation in the 1972 Pamplona Encounters. In the same way as the artist's other work in the show Accounting for Time (1996), it reflects the central place played by time in his oeuvre. José María Díaz Cuyas writes that Clocks can be interpreted as an artist's book, a photographic series or an urban action, reflecting the importance Valcárcel Medina has always given to process and experience; he is an artist who prioritises 'working itself', the 'act of producing and perceiving', over the creation objects and a vision of the work as a 'finished object'.

The 365 black and white photographs that make up the work document a year-long series of actions by Valcárcel Medina; each day he would position a different calendar clock, as a form of 'anti-monument' in some location in Madrid. These rectangular panels, suspended from the top of a pole, were divided into two symmetrically-divided vertical fields; on the left was the clock itself and the on the right an advertisement, while over the top was the name of the street on which the piece was installed. The artist photographed these actions without any particular concern for the technical qualities of the image. Their only apparent function – writes Díaz Cuyas – 'is to depict (with no regard for the framing, light or scene) the precise instant and place at which the photograph was taken', thus underscoring the inherent potency of the very act of photography. Clocks can therefore be viewed as a critical investigation of the contemporary urban experience and its inherent momentum. At the same time, however, to quote Yolanda Romero, it is a work 'about the creator's own life, about his routines and his time addressing the public time of the modern city (...), about the artist's discipline as a way of being in the world'.

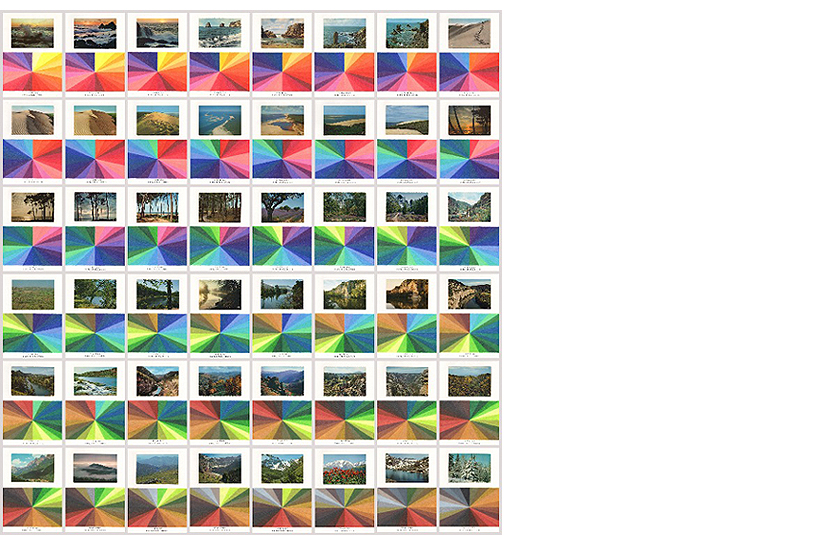

Inmaculada Salinas: Viral Diary (2020)

One of the underlying themes of Inmaculada Salinas's oeuvre is the visibilisation of art as 'work', often precarious, challenging the notion of 'productive time' in capitalist society. The third piece featured in this selection, Viral Diary, is a good example. This collage consists of 48 documents or sheets of paper. At the top of each one, there is a postcard view of a natural landscape, while at the bottom, a brightly coloured drawing recreates the effect of light passing through a prism. The sheets reference the first 48 days of the Covid-19 lockdown in Spain, when the public were banned from leaving their homes even for a walk. Each drawing consists of a geometric pattern made up of twenty-four triangles, one for each hour of the day. Each day, the chromatic range is modified by eliminating one colour and adding another. Through this slight variation, Salinas records the specificity, within the similarity, of the experience of each of those days when time was suspended and we became aware of our fragility, both as individuals and as a society.

Salinas has often used postcards in her work. Here, with their idyllic views of beaches, rivers, dunes and mountains, they operate as objets trouvés re-signified by the artist and endowed with a profound charge that is both poetic and political, since they refer to a desire whose realisation was not only impossible but explicitly prohibited. The poetic and the political also converge in the subtitle ‘besos, abrazos, caricias’ [kisses, hugs, caresses], which appears beneath each of the 48 drawings alongside the date on which it was made. The words are taken from Desobediencia, por tu culpa voy a sobrevivir [Disobedience, Thanks to You I Will Survive], a piece written and published during the early weeks of the lockdown by Bolivian activist María Galindo. As Ángel Calvo Ulloa writes, it highlights the 'presence of a hand that not only executes, but above all, feels and shows itself'.